Published in CineAction magazine 2018

Fuck History, Let’s Dance: Richard Avedon in Paris, 1956

Man forgets that he produces images to find his way in the world; he now tries to find his way in images. He no longer deciphers his own images, but lives in their function. Imagination has become hallucination.

Towards a Philosophy of Photography -Vilem Flusser

Photography, which has so many narcissistic uses, is also a powerful instrument for depersonalizing our relation to the world; and the two uses are complementary.

On Photography – Susan Sontag

Richard Avedon Robin Tattersall and Suzy Parker, models, Place de la Concorde; Paris, August 1 1956

The picture was elaborately titled by Richard Avedon: "Robin Tattersall and Suzy Parker, models, Place de la Concorde; Paris, August 1, 1956." As John Berger said of a nude by Albrecht Durer: “The result would glorify Man but the exercise presumed a remarkable indifference to who any one person really was.”(1) By 1956 the American photographer Richard Avedon showed two models on roller skates on the Place de la Concorde exhibiting a particular kind of movement: carefree. They are youthful, deliriously in the moment, and only a little younger than Avedon himself who was then thirty-three. It is of course a fashion photograph meant for easy consumption in a magazine, but for that very reason there is something that we can learn from it about where American sensibilities were then, and the road that the country as a whole would eventually choose to take. Avedon himself ultimately embraced another path far different from the promise of that picture made in the summer of 1956. What can that picture tell us today?

Richard Avedon, Self Portrait, 1956

Avedon arrived at the concept of the image from three primary sources that he then amalgamated into a coherent, seemingly spontaneous photograph. Its primary source of inspiration was the work of Jacques Henri Lartigue, a photographer known primarily for his candid pictures of his wealthy family and friends during the Belle Epoque in France. His images of automobile and airplane races, fashionable ladies strolling in the park, and people jumping, skating, rolling and diving, created - via John Szarkowski’s influential exhibitions at MoMA – a moving portrait of the period seen by several generations of museum visitors. Avedon himself would help to promote Lartigue’s work by editing his first book, Diary of a Century - a labor of love that took several years. The second influence was the work of the Hungarian photographer Martin Munkacsi. In the late 1920’s and 1930’s it was Munkacsi who revolutionized fashion photography by rejecting Alfred Stieglitz’s and Edward Steichen’s more serious, formal, sober approach to fashion photography, that sought to approximate the high antiquarian tone of classical painting. He took fashion outdoors into the sunlight, or the pouring rain, asking his models to run and laugh directly into the camera – in effect bringing the spontaneity, fun, and play of the Kodak snapshot into the staid realm of fashion by cleverly affecting its formal cues, and staging them on location.

Martin Munkacsi, Jumping a Puddle, for Harper’s Bazaar, April 1934

The third element in the mix is the contemporaneous Hollywood musical brought to perfection by Vincente Minnelli, Adolph Green, Betty Comden, Arthur Freed, Gene Kelly, Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire alongside many master technicians that worked within the studio system in the Los Angeles “dream factory.” The obvious film that is referenced in Avedon’s photograph Robin Tattersall and Suzy Parker, models, Place de la Concorde is Shall We Dance (1937) where Astaire and Rogers wear roller skates and perform a brilliant set piece in a park created in RKO studios, dancing to Ira Gershwin’s Let’s Call The Whole Thing Off. Typical of the self-deprecating humor involved in this aesthetic they ended their set by falling into the bushes.

The male hand pointing right beautifully articulates the counterpoint of the woman’s scarf pointing left. Female and male balance each other out and the massive Place de la Concorde looks like an enormous stage with a small row of classical buildings in the distance like toy sets. Avedon’s humanist leanings are fully operational as the models tower above the man made landscape, their ecstasy a triumph of Western liberal democracy and liberty expressing a newfound freedom: sexual, social and economic, all wrapped up in one package and ready-to-go, as the Americans say. It is a triumphant image. The statue of Louis XV sitting heroically on a horse that stood gloomily in the center of the square has been replaced by a joyous American couple ready to set the world right. They aren’t just dancing, they are saying 'fuck you' to history. They are saying the moment is now, it’s here, let’s dance. History: FUCK YOU. Avedon's aggressively flamboyant image has a narrative at its heart and that is that the play and magic of childhood can be extended to an adulthood that is sensual, sexual and romantic indefinitely. It is a narrative that is democratically available to all who desire it. This is not a new narrative - or fantasy in the form of a narrative - but it is given a fresh makeover here, and history (symbolized by the government buildings in the distance), can now be seen as something literally and figuratively behind us, a mere backdrop, a picturesque antique from the distant past that we may use as we like. Is Avedon’s enterprise possible?

Henri Cartier-Bresson Place de la Concorde 1952

The Place de la Concorde was originally named Place Louis XV when it premiered in 1755 and was used mostly in ceremonial parades. Thirty-four years later the octagon shaped square was used during the French Revolution as the place that housed the infamous guillotine, and its name was temporarily changed to Place de la Révolution. Marie Antoinette, Charlotte Corday, Georges Danton, and Madame du Barry were some of the many that were guillotined there. In 1794, in a single month, thirteen hundred people were executed there, their blood poured into the open gutters.(2) It is a place that was meant to celebrate the power of kings and then to celebrate their extinction at the hands of the revolution. What Avedon comes to celebrate is clear – it's a fresh start. That is what the image proclaims: this dance is meant to do away with history and its oppressive weight. Like the American musicals that it references, made during the same time period, it suggests that transformation and joy are creative possibilities that are within reach for all of us.

Funny Face, frame still, Stanley Donen 1957

It is the kind of ecstatic philosophy - free-market individualism - in action that we see in Funny Face (1957), the film loosely based on Avedon’s life as a fashion photographer for Harper's Bazaar and Condé Nast, in which Fred Astaire played Avedon. Stanley Donen's film astutely captures the charismatic charm of the master photographer and his model/muse. In real life it was the model Dovima, who famously posed for Avedon with an elephant that was his young protégé and muse. In Funny Face it is Audrey Hepburn, playing Jo Stockton, a bookshop assistant who is enamoured of existentialism - transformed to "emphaticalism" - and its blowhard leader, Professor Emile Flostre modeled on an amalgam of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, but caricatured as an intellectual poseur and playboy on the make. Joe Stockton is the "It" girl who conquers Paris despite the odds, and as to be expected, finally sees through the absurdity of "emphaticalism" with the help of Astaire/Avedon - or Dick - as he is called throughout the film. More importantly she is a witness first hand to the truth that dancing and posing for images can be a form of poetics and play in the face of the infinite. Like American jazz and abstract expressionist painting - that were contemporaneous with the film - dance and improvisation can become powerful expressions of the existential will to exist in the face of oblivion. The obtuse and heavy Flostre/Sartre and the light and nimble Astaire/Avedon are both philosophers but at opposite ends of the spectrum, and it is clear that "emphaticalism" does not stand a chance in the face of Astaire/Avedon's philosophy, that might be analogous to American pragmatism – a philosophy that he expresses, appropriately, not in books but in action.

Funny Face, frame still, Stanley Donen 1957

The Hollywood musical in its classical form was brought to perfection by Vincente Minnelli, Adolph Green, Betty Comden, Arthur Freed, Gene Kelly, Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, who, along with many master technicians worked within the studio system in the Los Angeles “dream factory.” Aside from entertaining mass audiences these musicals expressed a profoundly American philosophy of Pragmatism, espoused by William James and Charles Sanders Peirce in books, but expressed in the American film industry through a visual poetics of bodies in motion that had few equals – perhaps the only equivalent was in modern dance, such as the revolutionary work of Merce Cunningham, that also sough new forms for dance that incorporated the chaos and discontinuity of contemporary urban life. While these musicals affected an air of whimsy and lightness of touch they in fact signaled a radical revolution in art where “heaven” would no longer be linked to death cults. Death had been the center of attention from the ancient Egyptians and their Book of the Dead, to Medieval Europeans and their Book of the Apocalypse; from 18th European creeds of revolutionary martyrdom to 19th century romantic American landscapes that were strangely depopulated and saturated with mystical symbolism and religious meaning. As a riposte the American musical constructed a belief system that espoused a heaven-on-earth, full of earthly laughter, camaraderie, and pleasure, made possible through ecstatic dance that is both sexual and communal. In short, the American musical tapped into pagan, Pre-Christian philosophies, such as Epicureanism, and combined it with American Pragmatism, to create a seductive mixture of self-realization and happiness (the word is written into the American Constitution) in the here-and-now. While the philosophic foundations of the musical were radical, its content emphasized a conservative, even reactionary, retrenchment of traditional, patriotic, and family values, often temporarily usurped by lusty, male (heterosexual) braggadocio. But the central character always returned to the fold, usually ending his adventure in marriage vows. The tensions between the pagan/dance and the traditions of home/family were the motor that drove the engine of the classical musical, from Follow The Fleet (1936) to Meet Me In St. Louis (1944), and the template would only be broken by the filmmakers of the New Hollywood, most poignantly with Bob Fosse’s Cabaret (1972) and Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) that began a new chapter for the genre.

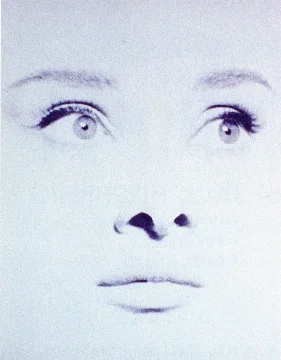

Unfortunately for Funny Face by the post-war era this philosophy of Pragmatism in action had showed itself to be fundamentally violent, destructive, patronizing and patriarchal, but the film is oblivious. This philosophy was the backbone of a strain of capitalism that did not recognize limits or boundaries and an insidious colonialism without moral restraints. Like all such enterprises it came home to roost, and seeped insidiously into the arena of sex and mating rituals. Astaire/Avedon explains Flostre's hypocrisy to Jo by exclaiming that the esteemed professor “is about as interested in your intellect as I am." The blow-up sequence in the film, in which Dick falls in love with the face of Jo that he develops in the darkroom - rather than Jo herself - anticipates Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up (1966) and its obsession with eroticism, image making, and the nature of the real where "imagination becomes hallucination." Unlike Antonioni, Donen and Astaire follow the predictable, and staid, romanticism of the fictional narrative - boy meets girl, etc. - to the very end - that is to kitsch - thereby undermining their critical observations, leaving them in the darkroom undeveloped.

Funny Face - the photograph that Dick falls in love with.

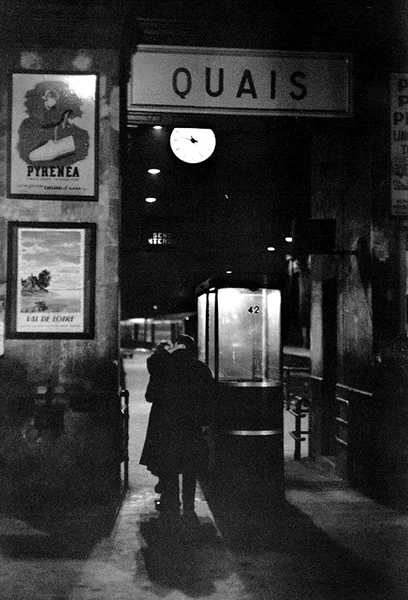

In the late fifties Henri Cartier-Bresson was also in Paris, along with Avedon, shooting his hometown. His images speak of a different kind of place. In Place de la Concorde (1956) we see the careful geometry of parked cars as they seem to fence off empty areas that are strangely depopulated, yet they are, as one would expect, loaded with history. Markers from the past, such as the obelisk in the foreground or the more distant Sacré-Cœur Basilica in the background act as a counterpoint to the neat rows of contemporary cars. Pictures such as Place de la Bastille (1958) more obviously let in the history that Avedon was so at pains to repudiate. But there is another image by Cartier-Bresson from the same year that calls Avedon’s bluff. On first glance there doesn’t seem to be much history in it at all. There are no marches against injustices to workers or students turning over cars because of some new colonial war. Something else is going on. In Untitled 1958 a couple is kissing in the street - an ephemeral, vernacular photograph surely - yet it is also a photograph that depicts history in the larger sense. How did Cartier-Bresson accomplish this?

Henri Cartier-Bresson Untitled 1958

Alain Resnais & Marguerite Duras, Hiroshima Mon Amour 1959 A Clocks split in half reflects on a window with Japanese writing, but the architecture is French - a palimpsest of times and spaces related only by memory.

The man and woman kissing are very much in the moment, wrapped up in their personal history while the larger History is put on hold. But Cartier-Bresson sees both the personal, the particular and its larger complex historical context, and he is able to articulate what he sees pictorially. The over-lit clock, due to the long exposure, hanging from the ceiling behind the word “quais" (platform) catches our eye. The reason for this is that the clock does two things: First the time itself is barely readable because of the overexposed light emanating from the clock face. Secondly the lovers were lit and partially silhouetted by the light from the clock illuminating their kiss. This light attaches the experience of the kiss to a duration within various interlocking histories. There is the history of this particular couple (which we will never know), then the larger social history of the time and place that they are inhabiting (which we partly know) in the European postwar period, the Cold War, the class antagonism that was building, the Algerian war, Vietnam, etc. Cartier-Bresson put these people into time because photography cannot do that passively. A photographer must construct a space where time is a player, as consciously fabricated as in a film by Alain Resnais. In Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) his great collaboration with Marguerite Duras, they superimpose a window reflecting clocks split in half and bisected horizontally, with Japanese writing, onto the facade of a French building from the previous century - a palimpsest of times and spaces related only by memory.

In the Cartier-Bresson image an advertising poster displaying modernist design and typography stands directly above another poster depicting a traditional landscape. The two posters and the couple are having a dialog thanks to Bresson's framing. Now, this is not unusual. If we go out in the street today we might find similar adverts that contain contemporary avant-garde designs next to conservative traditional posters, made to satisfy the wide range of visual tastes casually sharing the same wall space. But due to the placement in the frame, Cartier-Bresson creates a symbolic tension between the two conflicting design modes and the couple. This is a tension that is then echoed in the empty kiosk that separates the exterior world from the platform. The couple blend into the kiosk due to their dark coats - a kiosk that is strongly lit but empty suggesting absence, loss, or death.

This couple is free (in the philosophical sense of having free will) and stuck in time (in the physiological sense of the laws of physics). The clock is both an opening into a space because it is the present, and there is some freedom to choose in the present, and a death sentence from which there is no reprieve. This couple does what almost anyone would do under those condition; they seize the moment. Is it the right moment? We don’t know. The couple does not know, but the clock is ticking and they have stopped to kiss just between the outside world and the inside platform - they are in-between - suspended - putting history on hold long enough for one kiss - that's all they have - it's their story in one second.

What did Avedon see in the Place de la Concorde that August day? A couple dancing on skates who are not really a couple, but models that are being paid to act as if they were a couple (and as if it were winter even though it is August). There is the crew who helped him in the shoot: make-up people, wardrobe, hair stylists, drivers, translators, assistants, etc. In short, all of the things that are missing from the shot - that are behind the camera - are what might have made that shot interesting. If only someone had been shooting Avedon and his crew there would be something compelling there - perhaps. But the master photographer's overwhelming sense of romantic spectacle, his minute attention to detail, and his sense of complete control within the frame - his great strengths - are precisely what limits his image as it is locked into a rudimentary romanticism from which it cannot escape. Despite his location Avedon is at pains to negate tragedy - and he pays for that negation by submitting to the theater of fantasy. He is not aware that it is possible to include both fantasy narrative, or genre, and the contemporary documentary, or the historical, within the same image. Let's find an example that is from the same period where this occurs.

Three years after Avedon, Jean-Luc Godard also filmed a couple walking down the street, this time the Champs-Élysées, shot with a camera hidden in a bread cart. By doing so he incorporates the passersby who happen to be casually strolling down the street on a beautiful spring day in Paris in 1959, including one man trying to sell something to Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg as they flirt and talk. In the Godard film, as well as in the Avedon picture, they are actors, but Godard has done something very important that Avedon failed to do. He seized the opportunity to shoot his film guerrilla style on the streets using the random, haphazard reality of the moment. Godard said he shot his film in the style of cinéma vérité, as if making a documentary about the making of a gangster film. In effect Godard merges Avedon’s romanticism, and his emphasis on clear dichotomies, with Cartier-Bresson’s attention to quotidian historical detail, and his emphasis on the tragic and the unknown, and therein lies the charm and part of the genius of Breathless (1959).

Jean-Luc Godard Breathless 1959

What makes Avedon’s dismissal of the historical so damming is that in subsequent years American advertising, art, and fashion photography deviated only very slightly from the a-historical program outlined by Avedon in 1956. His photograph is a kind of template of an American idea, or ideal, that although he did not invent - it existed in embryo form - he used it without reflecting on its consequences. Its power is so pervasive and pernicious that it persists, in one form or another, to this day. To Avedon’s credit, he would be one of the first to move away from the sachyrine artificiality and aversion to historical realities, and its emphasis on individualism, that the image imposes as a fait accompli.

The dark side to this concept is clear when we remember that 1956 was the year that the war in Vietnam passed from French to American hands with no fanfare and little reportage. This was the year the Vietnamese, with American financial and military support, refused to hold elections (that would probably have been won by the Communists) and thereby set the stage for an attack by Communist-led guerrillas known as the Vietcong. It was also the year Graham Greene published The Quiet American in the United States, a brilliant and prescient indictment of colonial greed, moral corruption, and predatory sexuality in Southeast Asia. It is in Vietnam that the philosophy of American pragmatism showed its true face - that of a colonial master, in the British and French tradition, putting his house in order and the "natives" in their proper place, so they understand who's in charge. Greene’s novel remains unsurpassed as a moral critique of the war in the form of fiction.

Avedon himself traveled to Vietnam in 1971 and said, “... all of the people that I have photographed in the last year and a half have been affected by Vietnam – as has all of American life. Vietnam is an extension – unfortunately – of everything sick in America.”(3) One hears in Avedon's despairing language Joseph Conrad's cry: "the horror" from Heart of Darkness (1900), that would be re-deployed in Vietnam courtesy of Francis Ford Coppola in Apocalypse Now (1979) where Marlon Brando plays the mad, colonial emperor, Colonel Kurtz, who comes to believe he can save a people by killing vast numbers of them.

In 1975 the war ended, and the North and South were reunited in a Communist victory. In a sense the burdens of History in 1956 passed from European to American hands, just as Americans, or at least the population at large, were most eager to disengage emotionally from the historical, as seen not only in Avedon’s image, but those photographers who used their images to sell not simply a product but an idea. That idea is, in a word, "freedom." Freedom from history, freedom from class hierarchies, freedom from the urgency of death - and freedom to escape restrictions on the self, freedom to move ever forward into greater unlimited progress, greater upward mobility, greater unlimited power.

Norman Parkinson Couple Running Over the Brooklyn Bridge 1960

Elliott Erwitt, Paris 1989

Barefoot in the Park 1967 Promotional Poster

'That Avedon would choose a place as loaded with history as the Place de la Concorde is a credit to his chutzpah and to the brash, confident American sensibility (in 1956) that permeated the postwar years. Aside from Vietnam, the murder of Malcolm X, the Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King, the horrific atomization of a consumer driven culture, and the ascendancy of the corporate state and its resultant cultural stagnation, were still lying ahead, in what was to be the most culturally volatile moment of transition in the "American Century" - the term coined by Henry Luce, the man who started the magazines Time, Life and Fortune - and had a vast influence on the mindset of the American population in the 20th Century.

The 1960's ushered in Marshall McLuhan's concepts of "cool mediums" (to handle those cold wars), the "global village," "instant communication," and "instant simultaneity" - but these seemingly positive situations created a paradox. For example, while this "instant communication" might provide an unheard of horizon of progressive and emancipatory experiences it also created a tribal sense of dread, both existential and generalized. The reason being that - as McLuhan himself made clear - in a world of instant communication one can, at any moment receive a message that means "Panic! Start running now!" New means of transport and communication would create a permanent sense of dislocation and displacement as much as they would facilitate movement. The problems - clearly identified in the postwar period by writers as different as Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Hannah Arendt, and Herbert Marcuse - were a rapidly diminishing human agency and political freedom, and the paradox that as human powers increased through technological mastery and humanistic inquiry, we were less equipped to control the consequences of our actions. A paradox that today has reached critical mass.

Richard Avedon, Chet Baker, 1987

While there was common agreement throughout the 1960's that this was the situation at hand there was, as to be expected, radically different methods of finding a solution - if in fact there was a solution. What was understood was that the postwar utopian promises of universal access to information via the computer, electronic communication and media, along with presumably unlimited mobility - both vertical (freedom of movement within the social pyramid) and horizontal (freedom of movement across national borders) - all presumably facilitated a new utopia, but one that by 1968/69 was in deep crisis. Unfortunately this was not a situation that commercial photographers were able to articulate in their work. Quite the contrary - throughout the 1960's commercial photography delved deeper into banal fantasy images with a predictable emphasis on sexualized youth, beauty, success, sports, progress, etc. - in effect delivering the propaganda of the corporate state in palpable form to the masses. Avedon's image of two people on roller skates would become one of the templates for this kind of work.

While commercial photography sunk into simplistic fantasy art of the lowest order, artists in the same period created a Pop Art that was primarily ludic, superficial, self-referential and self enclosed - unable or unwilling to deal with the problems at hand. It is the independent filmmakers of the 1960's who took a far more interesting approach by subjecting their narratives to what we might call stress tests to see how they held up (Antonioni) - or they disassembled their plots within the film itself to see how they were put together (Godard). Perhaps it was because they were involved in a narrative medium, tied to theater and genre, that they were able to achieve this “renaissance,” now known as the art film. Their work was part of a whole group of films made around the same time, by mostly European filmmakers, but not limited to them, that addressed the collapsing social norms - or the "social contract" - that was undergoing radical transformation in the post-war era, and that by the late 1960's was beginning to unravel. That is one of the things that made that period so scary and so uncertain - no one knew where this unraveling would lead.

Keeping that in mind, we can see the following films as "portraits" of this disintegration made at the time that it was happening: Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point, Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend, Liliana Cavani's The Cannibal, Richard Lester's The Bed Sitting Room, Marco Ferreri's Dillinger is Dead, Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls, Federico Fellini's Toby Dammit, Glauber Rocha's Entranced Earth, Jane Arden’s The Other Side of the Underneath, Pier Paolo Pasolini's Pigsty, Ken Russell's The Devils, Elio Petri's The 10th Victim, Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool, Don Levy’s Herostratus, Kenneth Anger's Lucifer Rising, Lina Wertmuller's Don't Sting the Mosquito, Nicolas Roeg and Roger Cammell's Performance and Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Love is Colder Than Death (among others). These films all dealt with contemporary society from what we might call an outraged critical perspective that sought to explore its tragic contradictions from inside the society that created them, and thereby establish a new aesthetic paradigm through critical analysis of that immediate reality, rather than through an abstract or conceptual reconfiguration of artistic practice.

Richard Avedon, Aretha Franklin, 1968

Significantly Avedon’s work would be much copied but would not be repeated, not even by Avedon himself, who turned mostly to in-house studio portraits. It would be up to other photographers and filmmakers to take up the mantle of that photograph shot in Paris in 1956 and reformulate it in the marketplace for contemporary tastes, translating it to the theater of advertising photography and the commercial feature film. We see this in photographs by Norman Parkinson Couple Running over a Bridge, (1960), and in Elliot Erwitt's Paris, (1989); and we see it again in the films by Neil Simon's and Gene Saks' in Barefoot in the Park (1967) and in Blake Edwards’ Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961). All of this work shows the power of Avedon's original image as it captures the essence of a collective fantasy in a single shot. That Avedon was well aware of this fantasy aspect, and its lucrative commercial appeal, is clear from an interview from 1993:

Richard Avedon: Carmel Snow (Editor of Harper's Bazaar) said,' Do you realize what Harper's Bazaar and your work mean to the economy of France? We have to recreate the sense of an illusory Paris!'

Question: A sense of... Champagne?

Richard Avedon: Exactly. I photographed a prewar Paris (in 1956), a Lubitsch Paris, a Paris that did not exist. And it worked! The buyers came, the world came back to Paris hungrily. (4)

Richard Avedon, Fashion Work, 1956

In the 1950's the buyers came for a fake Paris of the 20's and 30's that no longer existed as its moment had passed, but what they wanted was not even the historical city in this period - that was after all still in the traumatic postwar convulsions of WWI and the Depression - but rather the imagined romantic Paris of Hemingway and Hadley, Stein and Toklas, Gerald and Sarah, Picasso and Olga, etc. The film work of Ernst Lubitsch, name-referenced by Avedon, had a very European sense of irony and fatalism and a droll regard towards its own deep romanticism; there was an aristocratic, faux, disdain - that was meant to be amusing - for the vulgar and sordid hunger for casual sex, luxury, and beauty. Ironically later in the century photographers such as Elliott Erwitt made people hungry for the Paris of the 1950's: the Paris of Jean-Paul Sartre's and Simone de Beauvoir's salons, Jean Genet's radical demimonde, Jean Debuffet's Art Brut and Ed Van Der Elsken's romantic bistros. Erwitt and the more prosaic photographers of a later generation recycled Avedon's original work of the 1950's, turning it into a marketable style that could be recycled, with minor changes, indefinitely. Throughout the 1960's Avedon himself made use of a strobe light in front of a white seamless, eliminating the outside world altogether, concentrating on the facial and physiological demeanor of the major and minor players in the American, and Vietnamese, scene of the following decades, collecting a kind of psychological portrait of his era.

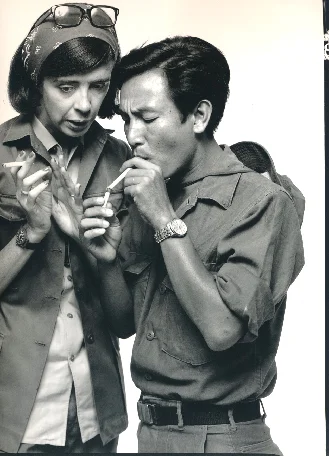

Richard Avedon, New York Times Correspondent With Nguyen Ngoc Luong, Interpreter, Saigon, Vietnam, April 1, 1971

In this body of work, individuals dressed for their professions, enter the white void of Avedon's seamless space, turning their clothes into costumes and their lives into theater. Their energy is held for a second, their heavy, thick drama put on hold, while Avedon got his shot. This body of work - one of the photographic treasures of American art - was both intimate and formally removed, deeply caring and involved while also clinically dissecting psychological nuances that were measured in fractions of seconds. After a session, that might last only a few minutes or several hours, the subjects leave his stage and go back to their dense destiny but Avedon has captured a slice of that drama in a black and white negative as thin as human skin. Meanwhile his fashion work, that was so crucial to his early development and sensibility in the 1950's, had by the following decade become a lucrative business and a hardened shell - an armor against the violent world of everyday life - that photojournalists in the field were confronting with a dramatic power and emotional intensity that far surpassed the parochialism of fine art photography, or the fetishistic calculations of advertising. It is in the work of Larry Burrows, Susan Meiselas, Philip Jones Griffiths, Diane Arbus, William Klein, Vivian Meyer, Nigel Henderson and Robert Frank among others, that a revolution occurred within photography that started a new chapter for the medium, and by inference, closed another one.

Avedon seemed caught between worlds: Art and commerce - fashion and photojournalism - the theater of post-war romance and the hard existential confrontations of the 1960's. But he was also determined to create a space for his work that absorbed the best of all traditions regardless of their seeming incompatibility. Picasso did this regularly with his paintings so it seemed reasonable to assume that it would be possible to do it in photography. His images were as direct as those of a photojournalist and as carefully constructed and fastidious as those of an advertising photographer, without being either. In short, Avedon's ambition was to eradicate photographic boundaries and hierarchies across all genres and types - that is between high and low art, and art and commerce - as did many other artists in the same period. But of course those boundaries were never destroyed but merely reconfigured to new parameters (set by those in power), as they are very much with us today. This was a fundamentally American, democratic idea (or ideal) - coming from Emerson and Whitman and translated into photographic space by Jacob Riis, Helen Levitt, and other socially conscious photographers who placed their subjects above their careers or the aesthetic paradigms of their time.

In Avedon's case this socially conscious work, akin to photojournalism, was then worked on in the darkroom, into a precisely rendered, highly formal work - often shown in large scale on a wall - that insisted on being high Art. These self-evident contradictions that Avedon navigated were not a mistake, but rather a duality that was an essential part of the work's power. Jane Livingston: “Avedon remains a member of a different tradition, even a different era. It is not so much that he is of an older generation as that his philosophical and psychological concerns belong to a larger, a late millennial stream of moral and aesthetic ideals. Avedon sits more comfortably among the many postwar writers, poets, actors, playwrights, philosophers he has photographed along the way – those members of a modernism whose traumatic severance from the romantic tradition has often been the very subject of their work ...”(5)

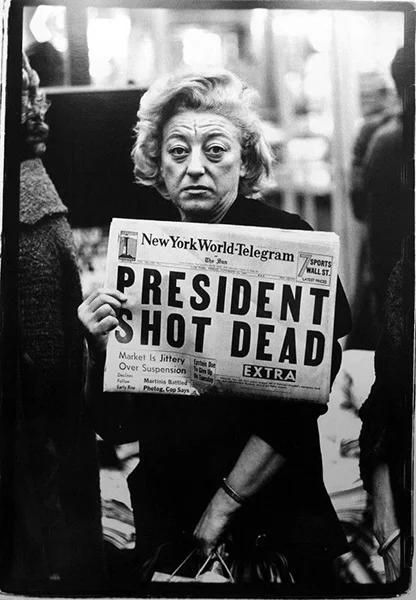

Richard Avedon, Times Square, New York City, November 22, 1963

That “traumatic severance from the romantic tradition” that Livingston acutely describes is something we see full force in Avedon’s image from 1963, titled Times Square, New York City, November 22, 1963. History suddenly comes back front and center as a woman shows the camera the headlines from that day: President Shot Dead. The expression on the woman’s face, the matter-of-fact American vernacular used in the headline, and the oversized font are chilling and perfectly capture the time in a way other pictures do not.

Typically, Avedon orchestrated the shot, taking copies of the paper to Times Square and asking people to pose for his camera, creating a dialog between photographer and viewer that is normally outside the domain of photojournalism. In a sense he used history to establish an exchange of looks across the frame – and now the subject is no longer an anonymous model but a fellow New Yorker – a traveler who had kindly stopped so that he could take her portrait as she looked across the no-man’s-land of the picture plane with something to say. This time Avedon isn’t just looking and framing, he’s listening. That makes all the difference. It is a history lesson in photography worthy of Cartier-Bresson or Helen Levitt, two masters that he revered. Yet Avedon never abandoned fashion photography in favor of documentary work, as he was comfortable moving from one to the other, but the fashion pictures from the sixties onward would be informed by his documentary work (and vice versa) in a way that helped shape his signature style.

For Americans in 1963 the days of 1956 were suddenly very far away and would not return again. History came back announcing itself, as it often does, with a funeral march, and America plunged hand over fist into history in the 1960's in a way that would mark the country for the remainder of the century, and beyond. It would prove a maelstrom from which the self-assured America of the postwar years would not recover. The country itself would, of course, pick up the pieces and refashion a new social matrix, but it would prove a very different place that Avedon himself explored in subsequent bodies of work, such as those seen in the now classic book, "The Sixties."

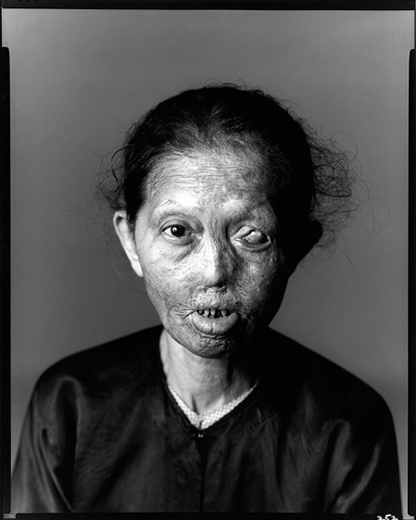

In his photograph Napalm Victim, Saigon 1971 Avedon confronts the historical in the present tense so we see the effects of the then often used term “napalm strike” up close and personal, with a large format camera that gets the details - and that intense look across the frame, from subject to photographer, that Avedon never flinched from. The players in the American “theater of war” (a term used by the American Defense Department) found their photographer – and it turned out to be the same person who had photographed two models on roller skates in Paris fifteen years earlier, but of course, not the same person at all. Avedon had grown up.

Richard Avedon, Napalm Victim, Saigon 1971

John Berger, Ways of Seeing, Penguin Books, 1973

Simon Schama, Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. Vintage, 1990

Gloria Emerson, Avedon Photographs a Harsh Vietnam, NYTimes, May 9, 1974

Michel Guerrin, “Interview with Richard Avedon, Le Monde, July 1 1993

Jane Livingston, Evidence 1944-1994, Random House, 1994.