The Biggest Film Biographer in the World: The Films of Ken Russell for the BBC

Published in CineAction magazine 2010

Passion paralyzes good taste.

Susan Sontag

Dante's Inferno Title cards that simulate early 20th century film.

MONITOR AND OMNIBUS

Ken Russell’s career as a filmmaker began with a series of short films made for the BBC starting in 1959 with a black and white documentary on the little known contemporary English poet, John Betjman’s London, where the eccentric writer showed off his hometown. Russell’s first film that dealt with music, a subject that would preoccupy him for the rest of his life, was a short film that featured the work of Gordon Jacob, an equally obscure English composer, teacher, and music historian. The series ended in 1970 with a color, feature length film on the life of Richard Strauss, Dance of the Seven Veils – the title references Strauss’s fever-pitched opera of sexual hysteria, misogyny, necrophilia, and revenge, Salomé (1905) based on Oscar Wilde’s play from 1891.

Russell’s eleven year span of work at the BBC constitutes one of the major bodies of cinematic work in the 20th century. The films were first made for the series Monitor (1958-1965) and then for Omnibus (1966-1970). A list of some titles gives a hint of their depth and range: Bartok (1964), The Dotty World of James Lloyd (1964), Scottish Painters (1959), Shostakovich: Portrait of a Soviet Composer (1961), Journey Into A Lost World: Mary McCarthy (1960), The Strange World of Hieronymus Bosch (1960), Shelagh Delaney’s Salford (1960), Lotte Lenya Sings Kurt Weil, (1961), Don’t Shoot the Composer: Georges Delerue (1966). One of the most fascinating films from the series was Pop Goes the Easel (1962), a 45 minute portrait of the young British pop artists then residing in London, including Peter Blake, Derek Boshier, Peter Phillips and Pauline Boty. The latter was one of the few women pop artists in a field dominated primarily by men. She died very young, and so this film is the only record we have of her, aside from a brief cameo appearance in Alfie (1966).

POP GOES THE EASEL

In Pop Goes the Easel each of the four artists was given their own segment. This is David Allan Mellor: “In their segments they (the men) coolly mime the fascinated poses of fandom and masculine heroics drawn from cinema’s past.”[i] They also indulged very seriously in the clichés of large cars, guns, and speed, often associated at the time with American popular culture. Russell nevertheless put their “heroics” in quotation marks using camera angles that mimic the traditional shot selection of adventure, or epic cinema, but placing these shots in a mundane, English context, such as a park or outdoor market, so they became absurd – the self-deprecating dry humor had a decidedly British sensibility.

Boty’s segment is completely different as she never talks about her paintings and is never shown at work. While some have attributed the label sexist to this aspect of the film, it seems highly unlikely since some of the artists featured in Russell’s Monitor series were not only women but outspoken radical feminists, such as the playwright Shelagh Delaney (A Taste of Honey, 1958) and the American dancer and political activist Isadora Duncan. The reality is far more interesting. Russell and Boty discussed her segment and decided to collaborate on a short film that is a “day in the life” – a popular format of the period – but then they turned that very earnest style on its head by replacing day with night, in effect opening the door to subconscious narratives.

Boty’s sequence starts with her in a very long, dreamlike, circular hallway – actually the offices of the BBC – laying out her drawings and paintings on paper on the floor. This is a very typical activity in art school so the teacher can see the work just outside the classroom for a quick critique. Boty had just finished the Royal Collage of Art three years previously. Before she finishes laying out her art a group of very serious adults come and step on her work. She slaps one of them, a woman, on the face. Then a creepy, older, androgynous woman in a wheelchair comes toward her with apparent malicious intent. She is dressed in black with unusual dark glasses, like the assassin from the future in Chris Marker’s La Jette (1962). Boty runs away down the circular hallway and finally escapes into an empty elevator, but when she turns the woman in the wheelchair is inside the elevator with her, and comes toward her. As Boty reaches for the emergency phone she wakes up in bed to the sound of her doorbell. There is a cut to a young man ringing the bell who goes to wait for her to come out by sitting down on a stone garden sculpture that looks like a sepulcher in a cemetery. He looks up at her window and Boty makes an appearance at the window fully dressed and made up in front of another stone figure – part of the building’s decorative work – fading from the elements into ruin. The film is accompanied by a wonderful score of distorted electronic music produced by the BBC Radio Workshop that also had a hand in the soundtrack to the popular Dr. Who series, and influenced the sound distortions and layering process in Sgt. Pepper five years later.

What are we to make of the Boty/Russell collaboration? The film had its detractors including the writer Sue Watlin who, in her book on Boty’s work, quotes the film historian Laura Mulvey: “Woman could be the bearer of meaning, not the maker of meaning.”[ii] Just how one can achieve one without the other is something neither Watlin nor Mulvey explain, since it seems likely that everyone who is alive is both making meaning and bearing meaning at all times, even if they are not aware of it - those who are aware are sometimes referred to as artists.

This is David Alan Mellor: “In Ken Russell’s 1962 documentary she (Boty) back-combed her hair before a mirror, a fantastic, mythical, flora, re-born from one of Leonara Fini’s paintings from the close of the 1930’s into the epoch of Pop. Boty appears in direct contrast to her male fellow RCA painters…as she is located within troubling narratives of eccentric femininity drawn from the cinema’s past…Her masquerade in Russell’s film…instances a certain idea of the production of beauty; precarious and excessive at the same time, rooted in representation and paradoxically forecasting the performed photo-mechanical comedies of female identity (Cindy Sherman in particular) of twenty years in the future.”[iii] Mellor’s astute analysis of Boty’s intention is on the mark but what he does not mention is that Russell brought his own eccentric antiquarian sensibility to bear on Boty’s very contemporary Pop ethos. This made for a strange and extraordinary hybrid film where death appears in several forms, from a specter in a wheelchair, to the modern coffin/elevator, to the Victorian stone sepulcher outside her apartment that is italicized when the young man gets up from it, and Russell holds the shot so we see it empty from above – a stone figure of a woman reclining and sinking into the ground and eternal repose. Boty’s collaboration with Russell – her nightmare – was unfortunately prescient but also charged with insightful, uncomfortable, critical insights, very much like her artwork. Pop Goes the Eeasel mimicked the Pop aesthetic of the moment, especially in its use of quick discontinuous editing, flash cuts, and dislocated urban montages that brought front and center the collage aesthetic that was the foundation of British Pop art.

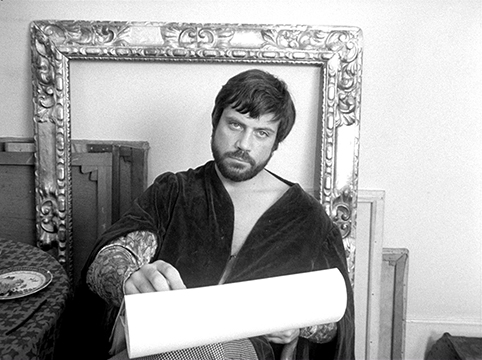

Ken Russel shooting Isadora, the Biggest Dancer in the World

KALEIDESCOPIC BIOPICS

The works that Russell made for the BBC are creations of the 1960’s and chart his first artistic maturity. This was a cinematic era that was in many respects in reaction against the middling and overly plotted films of the studio system that Francoise Truffaut in 1954 called “le cinema de papa.”[i] This traditional cinema – heavy on accepted narrative arcs and easy to read emotional exposition – originated in Hollywood but had derivative versions worldwide. While there were exceptions in England to this homegrown mediocrity, such as Brief Encounter (1945) and The Ladykillers (1955), the great majority of films made by the British studio system in the post-war era were hackneyed and lacked a sense of real time and place.

This was a tragic loss as that time period was fascinating, as we can see in the surviving documentary films and snapshots. Unfortunately this treasure trove of cultural information was literally covered up by the studios with generic sets and painted backdrops. Here is Russell describing these works: “There were the Ealing Film Studios where all those overrated comedies that give such a bogus view of British life were churned out – and studios like Riverside and Hammersmith where upper-class musicals like Spring in Park Lane and Maytime in Mayfair were artificially inseminated into being.”[ii] “Whether the location was Lavender Hill, Kentish Town, Pimlico or Mayfair, it was usually the same set revamped on the back lot. The characters were interchangeable. Most of those films were weak situation comedies in search of an identity.”[iii] Russell’s maturity came slowly over a span of years. At first Russell “was not allowed to show them (the main subjects) as we had to show just photographs. It was a very purist documentary. One had all the boredom of two decades of English documentary behind one to shake.”[iv]

One way young British filmmakers shook off those two decades of boredom was by a radical renunciation of the theatrical underpinnings of British films as seen in the Free Cinema movement, that mixed documentary and staged scenes to the point it was impossible to tell where one began and the other ended. Actors who had been given a character and a situation intermixed with people in social situations that were real and the actors then improvised freely. These films went much further than Italian Neorealism that was still tied to elements of melodrama, conventional establishing shots, and traditional musical cues. With films like Tony Richardson’s Mama Don’t Allow (1956), Karel Reisz’s We Are the Lambeth Boys (1959) and Robert Vas’s The Vanishing Street (1962) British cinema dove into the deep end of the New-Wave moments across the globe mixing avant-garde cinema with the close observation of ethnographic films.

The term Free Cinema refers to the fact that usually the crew and actors worked for free, and the miniscule budgets were covered by the British Films Institute, so in effect, the films were done for free. The term also references the fact that the films would be free of the conventions and formulas associated with large budgets. This group was separate but analogous to the British New Wave, or Kitchen Sink Films. They got that sobriquet due to the fact that dirty kitchen sinks piled high with dishes had not been seen before in the genteel and fantasy laden post-war British films that Russell described so well – what the Italians called “white telephone films” - but suddenly with the Kitchen Sink Films those clogged and filthy sinks were front and center, and people took notice. The writers who provided the screenplays for these works were part of the “angry young man” movement in England and their work was motivated by a desire to eradicate the staid, polite, traditions of British novels, theater and cinema by introducing a harsh realism, so people spoke – or in some cases remained silent – as they did in real life, using slang, obscene language, non sequiturs, and vulgar double meanings. The young writers sought to use actual contemporary neighborhoods rather than fictional locations, speech rather than rhetoric, and episodes rather than stories.

Russell went in a different direction entirely, highlighting the theatrical aspect of his films and pushing the artifice of that long established British tradition, the play, into multi-faceted works that resembled Restoration dramas in their unabashed, baroque, intensity, obvert sexuality, and dark, sarcastic, humor. He then combined this highly theatrical staging with traditional documentary use of photographs, paintings and voiceover narration, to tell a story. Russell described these works as “kaleidoscopic biopics.”[v] It is this “kaleidoscopic” or collage aspect that made the films fresh and modern.

It took him some time to reach maturity as an artist and he was fortunate in having as his producer for the Monitor series, Huw Wheldon, who would prove to be an ideal mentor. Wheldon was down-to-earth to a fault, knew his film history inside and out, was open minded, intelligent, and had a sense of humor. For an unschooled maverick filmmaker from the wrong side of the tracks like Russell, who was trying to find his way, Wheldon was the right teacher at the right time. Russell returned the favor years later, dedicating his autobiography, Altered States (1989), “With thanks to Huw Wheldon.” He knew that without Wheldon there would have been no “Ken Russell, film director.” This is Russell describing his apprenticeship at the BBC: “Over the years we were given the freedom to experiment. Gradually, we were allowed to show the hands of the composer playing, then the composer in long shot, still never speaking, intercut with newsreel material. Then we were allowed to show them speaking. They turned from little documentaries to quite long feature films. The programs were 45 minutes and there were usually four items to them. So you can see the films were very short to start with. As our films got longer they got more ambitious.”[vi] For some people at the BBC, such as Wheldon, Russell was a welcome breath of fresh air, someone who was set to revitalize its mission and its brand, while bringing in younger viewers, along with college educated professionals looking for more adventurous fare. This was exactly the audience the BBC was after. But for others Russell was a provocateur, a loose cannon who would, sooner or later, get himself and the BBC into trouble. This is precisely what happened in 1970 but by then Russell was already an established filmmaker who needn’t look back but forward to some of his best work.

Russell’s earlier and more personal short films such as Amelia and the Angel (1957) showed an intense and precocious talent idiosyncratically able to channel a very British Victorian/poetic sensibility that was also self-reflexive, ironic, and modern – an unusual combination. Amelia and the Angel seemed to permeate everyday places such as parks, abbeys, streets and humdrum middle class interiors, with the character of lived experience. Russell seemed to already have his keen eye for obsessive framing, careful observation of details, and a strong sensitivity regarding people’s interior lives, allowing his actors space to create a character. Russell had started his career as a still photographer, taking part in publishing photojournalistic essays for the Sunday supplements. True to form Russell also used his talents to photograph everything from bicycle races to naked female models for Men Only Magazine. But Russell’s passion was always directed toward the myth-making element of cinema, not the descriptive qualities of photojournalism or erotic photography. But from his relatively lucrative work he was able finance his short films and support a family.

By the time Russell arrived at the doorstep of the BBC in 1958 he was already 32 years old, married with two children. He had made three short films that were his portfolio that got him in the door, and he had also done time in the Royal Air Force and the Merchant Navy. Russell was born and raised in Southampton, a sleepy port town south of London. His father was distant, irascible, and prone to rages so Russell spent a lot of time at the local cinema with his mother who was mentally ill. He attended the University of East London where he studied photography. Although he harbored a childhood ambition to be a ballet dancer it was not to be and he joined the Monitor team, helmed by Wheldon, who had been impressed by Amelia and the Angel and decided to give Russell a shot.

The new documentaries for the BBC, using black and white 35mm film, were to be free of the stodginess and talking heads that were a regular feature of programming in the post-war era. By then these conventions were beginning to look old fashioned and contrived, and the new work, as envisioned by the team, would be more dynamic, using lighter, more flexible equipment common to Cinéma Vérité, with a greater use of quick cuts that were coming into vogue via the French New Wave. In short, they would be “modern” biographies of major artists, writers, and composers, concentrating on British lives but not limited to them. There was to be a voice over narration that was explicitly an authorial voice, as was typical of documentaries then and now, and there was to be use of extensive historical material made available through the BBC archives.

One aspect of the series that would be new and untried was that there would be re-enactments of important events in the biographies in which actors would play parts in costumes and in realistic settings. At first these were not speaking parts with the voice-over having dominance. When the subject of the film was a composer Russell would use particular sections of music, from specific time periods in the composer’s life as a catalyst and as musical cues for the structure of the film itself. As Russell put it, the form of the film would be dictated by the content, that is, by the biographical subject.[vii] For example, a film about Edward Elgar would be romantic, reserved, melancholic, and heavily feature the landscape of the English Midlands, while a film about Claude Debussy would be urban, modernist, ironic, humorous, but with a fundamentally tragic core. The narrative flow in the biographies gives way at certain points to extended lyrical reveries set to music. While these poetic juxtapositions of image/music had been seen previously in avant-garde films such as Kenneth Anger’s short film Eaux d’Artifice (1953), Russell used this technique as one aspect of a multi-faceted work that had a solid story arc as a foundation.

While biographies of artists and composers were an established genre by 1959 they tended to emphasize dramatic, or melodramatic, aspects at the expense of the bleaker, more brutal historical conditions of the period, that filmmakers assumed audiences either did not want to see, or were too unprepared or naïve to understand. The result was that the main emphasis usually featured basic romantic plots and intrigue with a traditional story arc that came from the 19th century European novel. Russell advanced both extremes at the same time, that is, the hard realities of the life and the brutal politics of the period, with personal drama pushed to the level of operatic hysteria, verging on burlesque, or satirical theater, while simultaneously pulling the documentary in to act as counterpoint. This layered, multi-faceted, non-linear narrative that Russell constructed would be a major contribution the film arts, leading the way for the subsequent work of Derek Jarman, Nicolas Roeg, and Peter Greenaway, among others. For example Carl Reisz’s French Lietenant’s Woman (1981), with a screenplay by Harold Pinter, was heavily indebted to The Debussy Film (1965) that used the same self-reflective shifts in time so one time period may comment on the mores and conventions of another.

In the BBC work the documentary archival material and voice-over act as the voice of reason, often leveling the drama, or putting it in quotations, with an ironic commentary, as the authorial voice-over would expound not only over paintings and photographs, as was the norm, but over dramatic re-enactments while actors performed in period costume. Their dialogue would then be muted while the voice-over calmly explained the situation, and once finished, would return to the action with sync sound. The collage aesthetic of the films came forward, often announcing itself in the credits, allowing Russell great freedom in the cutting and layering of the work.

Song of Summer Eric Fenby, the master's apprentice, learns to listen with a tuning fork by the beach. We sense his imaginative response through the tight framing of the head and the rocks on the water - the undulations of the water and of the sound become one.

THE ENIGMA VARIATIONS

When Russell first proposed a film on the life of Edward Elgar, who by the 1960’s was considered passé, it did not go well. Monitor was Huw Wheldon’s baby and as producer he had conceived it, hired all of the creative talent that made it work, and oversaw all details of the production. It was a popular show, coming on at Sunday evenings at 9:30PM, as it was one of the few things on the BBC that was challenging and unusual. Usually there were a few short documentary segments that filled that slot, but in rare times there would be one film that would take up the entire segment of time, but these were reserved for veteran filmmakers like John Schlesinger, who by 1962 was ready to move into feature filmmaking with A Kind of Loving (1962), one of the landmark works of the British New Wave.

By that time Russell had made 20 short films for the series and felt ready to move into longer and more ambitious films, and so he made his pitch to Monitor concentrating on Elgar’s forgotten prominence and the need to rehabilitate his status for a new generation of younger viewers. Wheldon replied: “The BBC is not a rehabilitation center. Your story is romantic cliché. It’s flabby. It has no backbone.”[i] Russell was stunned as he had wanted to make a film about Elgar for years and had what he considered a solid screenplay that was ready to go. Then Russell, in desperation, spoke about Elgar’s life, including the unlikely, but apparently true account, that while in his fifties Elgar liked to slide down the local hills in the Midlands using a tea tray. Wheldon at first couldn’t believe it, as he, like most people who were at all aware of Elgar, thought of him as the stuffy elder statesman of English music. Wheldon reconsidered and told Russell, “Forget your screenplay. Film it exactly as you told it. I suppose you will need actors?” The primary lesson that Russell learned from Wheldon was to condense his material to the point of abstraction and Russell was well aware of the trajectory toward the dissolution of narrative: “People are saying to me your films are too concentrated. Well, that’s the way they are, and that’s the way they’re going to be. I think the one thing that Godard did that was any good was to scrap continuity in Breathless. That was a great leap forward. Hollywood films all seem so slow and tedious and boring to me. I think they are the death of film. Film wants to get more concentrated than ever. We’re just on the borders of trying to get towards what it can be. I think it’s got to get so concentrated that in the end you don’t know what it’s about. It’s gone right within you, and you’ve got something out of it but you’re not quite sure what. That’s what I’m interested in doing.”[ii]

Elgar (1962) is a biography of the early 20th century British composer now best known for his cello concerto and The Enigma Variations (1899). Here Russell explains the latter work: “The theme on which the variations were based was never stated and people have been trying to guess its identity ever since. There are fourteen variations – each represent a person, for example, his wife is the first variation and the composer himself is the last; in between we have musical impressions of an amateur pianist, an actor, a music publisher, a pretty girl with a stammer, Bulldog Dan, a cellist, and a mystery person identified by ***; the perfect subject for a mini biopic.”[iii] The Enigma Variations would be a guiding light for Russell’s work from that moment on through the series of works as a whole, as it remains a masterwork of aural ambiguity and uncertain narrative clues. As Russell put it, the work was a kind of line on which to hang various ideas about people and their musical spirit without ever resolving the issue of the exact literal meaning of certain sounds. As in all of Russell’s work the physical aspect of the location takes on major importance as one can sense the hard English light, and feel the density of the wet, chilly morning air of the Midlands, as the camera surveys the desolate beauty of the British countryside – a landscape that permeates Elgar’s music.

SONG OF SUMMER

While the BBC films have a voice-over narration that is traditionally authoritative Russell treated his biographical lives obliquely rather than directly - we see inference rather than anecdote. Song of Summer (1968) concerns the relationship of the British composer Frederick Delius, who had become crippled and blind due to syphilis, to the master’s apprentice, the young Eric Fenby, who was an aspiring composer in his own right. Fenby took the delicate job of helping Delius to finish orchestrating his final works. Without his help Delius’s final five years would have been non-productive as well as physically difficult and emotionally traumatic. It is Fenby who provides the voice over narration set in the early 20th century, based on the young man’s memoirs. The paintings and drawings of Edvard Munch, a contemporary and friend of Delius whose work the composer used to decorate his house, populate the film and act as a sounding board to the delicate and difficult relationship between Delius and Fenby in a way that is never made explicit. Munch’s hardened winter aesthetic seems to permeate the summer landscape in a way that Fenby himself would not have been conscious of until much later.

ISADORA DUNCAN

In Isadora: The Biggest Dancer in the World (1966) the American dancer Isadora Duncan passes through various landscapes and urban views, from New York to Moscow, that correspond to the voice over narration but the staged scenes are shot in a documentary style with a hand held camera and the documentary shots have highly theatrical music cues to highlight their staged reality – again the presence of paradox and the collage aesthetic. Isadora Duncan is shown dealing with uncomprehending administrators in America, Europe and the Soviet Union - all oblivious to the creative impulse in her and in themselves, regardless of their political leanings. They manage over the years to wear out her body but not her spirit. Russell’s politics were fundamentally humanist. He loved creative people because of their unwavering emotional commitment to their work and to each other. When artists spoke truth to power he was with them every step of the way, and when they made a mess of their lives he fleshed out their emotional realities, putting them in a historical context, without being condescending or superior. Duncan’s overtly dramatic personality is given the floor as her complicated, emotionally overextended life, always playing catch-up on the run, is explored in depth, constructing a narrative that is as multi-faceted and complex as the subject.

Dante's Inferno Actors in costume in the midst of highly charged emotional scenes but with a voiceover calmly describing the action - the push-pull felt throughout the film.

THE DEBUSSY FILM

The most modernist and self-reflexive of the BBC works, The Debussy Film (1965) begins with a contemporary film crew arriving on location at a large chateau with a fire engine to produce the appropriately dramatic fake rain for a funeral procession. This film within the film is to be a biography of Claude Debussy, but Russell is now pushing the boundaries and he immediately blurs the lines between various periods in Debussy’s life and 1965. Even the overly dramatic fake rain carries over into the following scenes of a young Debussy (Oliver Reed) falling in and out of love in 19th century Paris (signaled by a one second shot of the Eiffel Tower) while reading overwrought Symbolist writers and going to art exhibits by Turner – an artist that much influenced Debussy’s dissolution of sounds within a very narrow tonal palette. Russell then cuts to a completely incongruous, baffling shot that he explains himself: “Near the start (of The Debussy Film) was a girl in a modern T-shirt being shot full of arrows by teenagers on a beach. You hesitated before you turn that off!” (Emphasis Russell). The beautiful but discordant shot of the very modern girl, being shot with arrows is clearly a reference to St. Sebastian as he is often depicted in classical paintings – it was also a favorite motif amongst Symbolist artists and writers, but here the subject has been turned into a sarcastic farce. But what could it possibly have to do with Claude Debussy, the man who created the first music – using consonances and dissonances - that sounds completely modern? Is Russell suggesting that modernity and religious mythmaking are fundamentally antithetical? Whose funeral is it? Why is the film’s director (Vladek Sheybal) so knowledgeable about Debussy and so discordantly droll, blasé and resigned?

The film moves from the fake funeral in the rain to the director feeding a line to a child playing Debussy’s son: “It seems he was a musician.” Even the director seems unsure. Reed/Debussy asks astute questions of his director about the composer often defending him against accusations of unfeeling carelessness, or outright sexism, in regard to his female companions. Just who is right in this argument remains an open question. The camera pans from the director absorbed in discussion to an outdoor luncheon on the grass in which the women in Debussy’s life set out to picnic in the summer of 1897. The transition in which the past and present cohabit works brilliantly to establish the emotional connections between actors and the people they are portraying and the scene collapses the two time periods. We see the short space between 1897 and 1965. Russell does not draw attention to his poetics, as does Ingmar Bergman who in Wild Strawberries (1957) has a camera perform a similar function. On the contrary the movement is quick and moves on rapidly to other business, nevertheless the poetics are no less effective.

This is made very clear in a scene that takes place at a contemporary party for the cast and crew. Reed/Debussy and the director step into an apartment where festivities are in full swing with the latest hit music on the turntable, You Really Got Me by the Kinks. The actors dance to the music with abandon and Reed, in a contrary mood, takes the Kinks record out and puts on one of Debussy’s most quiet and contemplative works. The actress Annette Robertson, playing Debussy’s mistress Gaby Dupont, challenges Reed’s move by using the music to do an impromptu striptease that delights her fellow players. To throw more fuel to the fire she throws her panties at the record player and the needle jumps as Reed/Debussy throws her daggers with his eyes. She clearly is challenging not only the actor, and by inference Debussy, but the very idea of serious music and what it might be used for. The juxtaposition of the Kinks with Debussy inevitably leads to the question of just what constitutes contemporary music. Are the Kinks Debussy’s heirs? Russell posits the question but does not answer it. The relationship of the actors beautifully mimics the relationship of Debussy to Gaby Dupont. The two identities fuse at that moment in a way that is both emotionally and aesthetically coherent and satisfying.

The Debussy Film brings to the forefront the film crew as a temporary, close-knit family of actors and technicians who are together for the duration of the shoot, at times playing games such as having Reed/Debussy in a “duel” with another actor, who plays Maurice Maeterlinck, the Symbolist writer who specialized in decadent fairy tales that would, presumably, stimulate adult imaginations. The two actors shoot each other with rubber darts shot from modern toys but speak their lines as if they were Debussy/Maeterlinck. Their absurd play, in a conservative 19th century mansion is telling about the childishness of actors on a set generally, but more importantly we begin to understand Debussy’s subsequent failure to produce work after that initial early success. His inability to reconcile that childish selfishness and narcissism which drove him on in his hungry years, with his adult emotional life, that he seems to have found unfulfilling, leaves him in limbo. It is in this period, starting in 1900, that he meets informally with a group called Les Apaches (The Hooligans) to discuss the new radical arts of the coming century, and discuss their status as “artistic outcasts.” Debussy spends his time playing games like an adolescent but can never finish his opera based on The Fall of the House of Usher, the Poe story to which he devoted the last twelve years of his life. The one opera that he did finish, Pelleas and Mellisande (based on Maeterlinck’s play of the same name), is so enigmatic and its themes of guilt, sexual repression - and the impossibility of reconciling with death - are so dark as to make certain the opera never received the attention it deserved in its own time. It would only find a few champions in the 20th century that saw the opera in Freudian terms and as the last stages of a decadent Belle-Époque strangled by social contradictions, sexual repression, and the unmitigated greed of a “gilded age” partying on a precipice where there was room only for a fortunate few.

By the early 20th Century when Debussy was creating his final masterpieces, his Symbolist, dreamlike music, after the destruction of Europe in WWI surely seemed like small potatoes - there was no energy present. His vital vocabulary of modern sounds had already been co-opted and enlarged upon by Igor Stravinsky, Alban Berg, Arnold Schoenberg, and others who revolutionized serious music. Debussy was caught between a century that he helped bring to an end, with original works such as his Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (1894) – the work that many, including Pierre Boulez, considered the first piece of modern music, and a new century that he seemed not fully able to comprehend. His retreat into boyhood games shows us in stark terms that are both comic and tragic, the end of the line. The funeral at the beginning of the film was, of course, Debussy’s own.

The Debussy Film 19th Century man and 20th century woman share the same space - problems ensue.

Dante's Inferno Gala Mitchell as Jane Morris - the cinematography perfectly captures the sexual charge in Pre-Raphaelite painting by immersing itself in its aesthetic.

ALWAYS ON SUNDAY

Always on Sunday (1965) was the biography of Henri Rousseau and is perhaps the most moving of the BBC films. The title refers to the then popular film Never on Sunday (1960) and to Rousseau’s status as a Sunday painter before retiring from his full time job as a clerk in a tax collector’s office in late middle age to pursue his beloved hobby full time. Rousseau was an iconoclast and a radical without aspiring to be either – he simply wanted people to like him and his work but was always encountering incomprehension, abuse, and ridicule. Completely out of sync with the academic Salon Art of his time – an art that he loathed – he was also the odd man out with the Impressionists, who found him a naïf, uninterested in the fugitive properties of color and light and the realities of the contemporary world that formed the basic subject matter of their work. Rousseau observed present day realities but only to expand the vocabulary of his incredible imagination. Russell used Rousseau’s letters in voiceovers that beautifully riff on the landscapes that the artist would have been familiar with.

Rousseau lived mostly alone, despite several attempts to get married. He felt the need of female companionship and intimacy to make his life complete, but it never seems to have never worked out for him, leaving him melancholic and cranky. Like many artists his main consolation was his work, to which he remained devoted. He lived long enough to know Picasso as a young man. The Spaniard had recently moved to Paris and was then working out the pictorial problems of one of the most radical, difficult paintings ever made, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907); a work that outraged everyone from friends to critics, to his rival Henri Matisse. Rousseau is said to have congratulated the fledgling artist on his new painting, telling him that they were the two greatest contemporary artists, Picasso in the Egyptian style and he in the modern style.[i] It is not known how, or if, Picasso replied to this astounding remark.

The uncomprehending audience of pompous twits during a gallery opening of Rousseau’s work – that included the masterpiece The Sleeping Gypsy (1897) – is shown in a burlesque manner by depicting the laughing gallery-goers as they would have been seen by Alfred Jarry, the great Proto-Surrealist writer, and Rousseau’s one friend who understood his genius and was able to write intelligently about it. The typically serious voice over commentary hilariously describes Jarry as a Pataphysical midget! This is a description that surely would have caused the highly sensitive Jarry to fire the loaded pistol that he carried with him on his bicycling tours of Paris.

Their moving friendship is visually developed in a few quick scenes that touch upon Jarry’s brilliant play Ubu Roi (1896) (King Ubu) that used comical, episodic, non-sequiturs in the tradition of music hall comedy. Nothing like it would be seen again until the silent experimental films of the 1920’s. It was obvious to the audience that first saw Ubu Roi that Jarry was making fun of those in power, skewering the proverbial stuffed shirts and over decorated pompous ladies who constituted the ruling classes in 1896. Russell juxtaposes the overbearing bosses and their lackeys on stage with those in the audience to full effect. When the women in evening gowns sitting in the front row nearly faint upon hearing the fist word in the play, “shit,” Jarry can only take delight in his small victory. His collage aesthetic, along with his sarcastic working class humor, is in many ways a precursor to Russell’s work, something we can see in his comic opera, The Pope’s Mustard-Maker (1907), the last work he completed before he died of alcoholism. The opera is loosely based on the legend of Joan, the female medieval pope, and contains the usual Jarryesque smutty jokes, puns, and lively songs full of wordplay and innuendo. The opera ends with the pope celebrating, in song, the spiritual value of enemas. The work was not staged in Jarry’s lifetime and remains unproduced. One day the world might be ready for The Pope’s Mustard-Maker, but perhaps the only person who could have done it justice was Russell.

Always On Sunday Henri Rousseau and Alfred Jarry seem to know they are doomed - and the child between them, painted by Rousseau, unites them.

THE HOLLYWOOD BIOPIC

Let us for a moment contrast Russell’s work with the typical Hollywood composer-biopic – a genre that illustrates an essentialist narrative so a life can be readily understood in 90 minutes. One example is Immortal Beloved (1995), a biography of Beethoven by Bernard Rose in which the composer’s music is made out to be about his frustrated love for a woman he can never hope to have and every scene in the film tediously reiterates the same absurd proposition. No attempt is made to try to understand who this very complex man was, or why he wrote the music he did, to say nothing his relationship with other composers and musicians of the time who admired his work. There is nothing regarding the elaborate and fascinating cultural and musical realities present in Germany at the time (1770-1827). For example, Beethoven used improvisation in performing his own work – a common practice at the time - but his playing employed hard shifts in mood, abrupt endings, and chromatic harmonies that went so far as to destabilize the tonal system itself. People at that time were fascinated by these new sounds and wanted to know more about them – what did they mean? Later composers such as Maurice Ravel and Dmitri Shostakovich built whole bodies of work on these innovations.

There was also the complex response at that time to Napoleon Bonaparte by the German intelligentsia, including Beethoven. Bonaparte was a specter that both enthralled and terrified them. None of these, among many other possible aspects of life in early 19th century Europe are touched upon. As for the immortal beloved herself she remains a blank cypher with no identity of her own except that provided by romantic cliché. Immortal Beloved is empty of everything except anecdotal melodrama, and the music is made to seem posturing and trite. Interestingly in the mid 1990’s Russell wrote a screenplay about the life of Beethoven based around the same characters, but did manage to include all of those qualities missing from Rose’s film. More to the point the famous immortal beloved speaks and gives her own opinion of Beethoven and his music, and her recollections, as to be expected, are not all sentimental and romantic, but realistic and critical to a fault. Russell was never able to secure the financing for his screenplay but not wanting to let good material go to waste he turned his work into a novel, Beethoven Confidential (2007).

Dante's Inferno Oliver Reed as Rossetti - framed within a frame while he composes.

Dante's Inferno Jane Morris and Dante Rossetti - an idyllic scene on first look - but the characters occupy radically separate psychological spaces despite their physical proximity.

DANTE’S INFERNO

The romantic intensity of feeling, and joy of life, of the biographical subjects is sometimes mimicked by Russell in the form of the film - a case in point is the Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet Dante Rossetti (Oliver Reed) in Dante’s Inferno (1967). He is first seen in the full fever of creative engagement. The camera movement and the heroic music share in Rossetti’s enthusiasm, youth, and promise. We see Rossetti’s first view of Jane Morris, his mistress to be and the subject of many of the Pre-Raphaelite’s best work, with energetic cuts and musical starts/stops, fully engaged with the romanticism of the moment - at one point even referencing the beginning of Jules and Jim (1962). The director is able to share in the romantic excess of his characters my mimicking their explosive creative temperaments, but unlike them he is able to pull back, in the documentary archival material, and see that romanticism in the context of other counter narratives that put that romanticism in historical perspective.

An example is the scene that follows that first meeting – a static interior shot in which Rossetti and his fellow Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood are making a large wall painting using Jane Morris as a model atop a ladder. Her idealized image, especially her incredibly luxuriant hair, would preoccupy much of the Pre-Raphaelite’s efforts for years to come. In this scene, that establishes her as the central muse of their group, she is frozen in a conventionally heroic neoclassical pose – a style much in favor by the Brotherhood – at which point she suddenly starts to chew gum and play with a Yo-Yo. In Russell’s work it is often women who throw a monkey wrench – or a spanner as the English call it – into the pretentious endeavors of egotistical men. Such a scene puts into doubt the Pre-Raphaelite ideology of classical order and ideal beauty that they so earnestly believed in and sought to create, or recreate, in their work. It suggests strongly that such endeavors are fantasies that have little or nothing to do with the everyday world as it is. Russell gives voice to two contradictory sentiments or voices within the same work to ecstatic effect for we can never be sure of where the film will go next, or where our sympathies should lie – rather we must think about it and come to our own conclusions.

DANCE OF THE SEVEN VEILS

Russell’s final work under contract to the BBC was a biography of Richard Strauss made in 1970, Dance of the Seven Veils. It is one of the most controversial films of his career as the work openly ridiculed Strauss’s Nazi leanings in a sarcastic, burlesque style typical of Russell’s work. While Strauss was more drawn to Richard Wagner’s bombastic, self-conscious grandeur than to fascist ideology per se, the homoerotic elements, and the caricatures of Weimar and Nazi Germany that Russell presented were too much for the established institutions of the time. The Strauss family refused to let the music be used for the film knowing that the film could not survive without it. The BBC after first supporting the film finally pulled it, and it was decided to ban the work from public view for fifty years, and then to allow its release intact. Russell’s work for the Omnibus series was done. He would return to the BBC as an independent filmmaker to make William and Dorothy (1978) a biography of the poet William Wordsworth and his devoted sister Dorothy, his muse and lifelong companion. He ended his run of films for the BBC with The Strange Affliction of Anton Bruckner (1990).

HE WROTE, HE LOVED, HE LIVED

We have in these dramatized lives of artists, poets and composers, along with their families, lovers and friends, evidence that they have created art, that they have loved, and that for a time they improvised a life from the raw materials at hand as best they could. Sometimes they did well and sometimes they made a mess of things, but that is already quite a lot. Stendhal, the 19th century French writer, penned the obituary to his own tombstone that reads: “He wrote, he loved, he lived.” It is quite short and to the point. Nothing more needed to be said because, in fact, there was nothing more - that was it - but apparently for Stendhal it was enough. Russell would surely concur, as Stendhal was a prose stylist that closely resembled the Romantic writers and the Lake Poets that he so admired, and from which he took inspiration.

Russell would tentatively move into features films (while still under the employ of the BBC) in 1964 with French Dressing, a comedy meant to be in the style of Jacque’s Tati’s Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953) and Federico Fellini’s The White Sheik (1956). Despite the film presumably taking place in Gormleigh-on-Sea, a rundown seaside resort the film was primarily shot at Elstree Studios near London and on location at Herne Bay, another seaside town. The plot centers around the local deckchair attendant – the lowest paid member in the entire town – who decides to turn the town’s fortunes around, as well as his own, by hosting a film festival, modeled on Cannes, and hiring a local film star from France to come and inaugurate the launch, and hopefully initiate a scandal, putting the festival on the map. Of course nothing goes as planned, and in typical Tati style, there is a lot of physical humor that the actors are able to deliver on cue. The main problem with the film was that the characters remained cliché types without ever becoming involved in their characters or their situation. The film seemed to be a series of skits that were beautifully framed but emotionally uninvolving. To add insult to injury Vittorio de Sica, Britt Ekland, and Peter Sellers would team up two years later to make After the Fox (1966) – a brilliant satire with more or less the same plot but the location shifted to a sleepy Italian beach resort.

In Italy and France Tati’s films had inspired many absurdist, amoral comedies in the sixties that did not travel well to England or the USA, where similar fare – such as the American beach comedies, or the British “knee trembler’s” of that period – had clearly defined, if simplistic, plots and a strong moral lesson that is learned at the end. The French and the Italians were hardly Puritans and their films were conspicuously adult comedies with only moral relativism, via Montaigne, as a philosophical framework from which to develop very loose plots and situations. With French Dressing Russell soon found himself out of his depths - as he described it himself: “The film industry was not ready to accept TV directors. Everything was done by the book, improvisation was frowned upon and there was little team spirit…a film director has to be a psychiatrist but it was too late as far as French Dressing was concerned – the film was a flop…a very unhappy film as far as I was concerned”

There are some comments by Russell here are that are worth pursuing. While improvisation in the theater was a commonplace in studio films it was very rare. For the American independent John Cassavetes in the US, the Italian Neorealists, and the British Free Cinema filmmakers improvisation was not only accepted but an integral part of the film’s form. Russell used improvisation and allowed his actors to develop their characters on the run, assuming he could then cut out all of the things that did not work. But the conventional studio films didn’t work like that - the cast in particular wanted their director to tell them (like a psychiatrist as Russell said) exactly what the problems and motivations were. The film was a failure at the box office and Russell returned to the BBC, bruised but hungry to give it another shot.

Russell got his second chance at features in 1967 with Billion Dollar Brain, the third installment in the “Harry Palmer” series. Palmer was a working stiff version of James Bond – living in a cold-water flat, wearing worn out suits, and never getting the girl. The first two in the series, The Ipcress File (1965) and Funeral in Berlin (1966) were superbly done cold-war narratives that were, like Palmer himself, lean, down-to-earth, and with brilliant craftsmanship all around, by cast and crew. While the franchise would seem ready-made for Russell – being about a cantankerous, working class outsider in a narrow niche genre straddling John Le Carre and Ian Flemming – Russell’s film seems to spin its wheels in a frenzy without going anywhere in particular, and while the ride is often enjoyable, the film is slight and lacks the substance of his television work. Nevertheless Billion Dollar Brain – like the previous Palmer films – was a financial success and Russell seemed to finally have his foot in the door.

The feature films and music videos that would preoccupy Russell for the rest of his life until 2011 would be uneven but often dazzling - reaching full artistic maturity with The Music Lovers (1970), The Devils (1971), Savage Messiah (1972), Mahler (1974), and his adaptations of three D.H. Lawrence works, Women In Love (1969), The Rainbow (1989), and Lady Chatterly (1993). The latter was an adaptation of Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover (1928) but with a new - one daresay feminist - emphasis on Lady Chatterly, as the title makes clear. The film fearlessly addressed the difficult choices available for women as the new 20th century, in all of its loud beauty, vaunted ambition, and tragic horror, dawned on “the lost generation.” The 20th century, seen from the vantage point of the 1920’s, must have been terrifying, dizzying, and tremendously exciting - far beyond what the imagination could muster - even Jules Verne and H.G. Wells were caught short. Russell got those conflicted emotions into his films as no one had before, or since. He would also use the same talented technicians, writers, and actors that he had with him for the early television work in his later films. Over the years this team would become his lifelong partners in the creation of a body of work that spanned four decades - invariably as members moved on or died the films suffered the loss and Russell found it difficult to find new collaborators that understood his aesthetic.

Russell’s later films would sometimes degenerate into bombastic caricature, as in Litzomania (1975), or Salome’s Last Dance (1988), which were humorous and visually imaginative but lacked the depth of the writing found in the early works. As the films went further into pastiche and parody they also lost the thread of the corporeal element that had made those works of his mature period so unusual, breathtaking, and radical. Another crucial missing element, that was sorely missed, was the documentary aspect that had made the films for the BBC so original and emotionally involving. Those biographies were challenging and intensely inventive, transforming the way we think of documentaries or the presentation of “reality” on screen. The works audaciously plundered the art of the past and quoted dramatic confrontations from various genres; classic art, films, music, and period styles were parodied, while using factual archival material from a wide variety of sources, deploying an immersive, poetic, non-linear narrative. That “kaleidoscopic condensation” that was so important in his early work seems to have gone missing, replaced by pastiche and naughty jokes.

But Russell was not short of ideas and he continued to make work that he financed himself, and shot on video, such as The Lion’s Mouth (2000) and The Fall of the Louse of Usher (2002) based on Poe’s short story but changing “House” to “Louse” in a typically broad gesture of comic anarchy. The later films incorporated music and droll comedy, emphasizing the artificiality of the sets and costumes, and exaggerating the absurdities of the horror. Yet, even in this later work we still see the ever-present beauty of the British countryside, the youthfully sarcastic humor, and the charms of his actors; but in these final films he also kept a more insistent, mordant eye on the absurdity of the human condition and the brevity of life. He died in 2011 while in pre-production for a film to be titled Kings X.

Whatever the shortcomings of his later work in Russell’s mature films there was what we might call, with apologies to Harold Bloom, an exuberance of influence, that delighted audiences because it challenged them to understand places, times, and people that were as complex, intriguing and curious as themselves and their own era. From the vantage point of the early millennium Russell’s best work looks more modern, more engaging, more alive, and more intelligent than anything in contemporary broadcasting media or cinema. Those films are teeming with a sense of immediacy and vitality and, in spite of the didacticism inherent in the initial project, at least as it was originally conceived by the BBC, there is still much that we can learn from them.

[1] Sue Watling, David Alan Mellor, Pauline Boty The Only Blonde in the World, Whitford Fine Art, 1998

[2] Sue Watling, David Alan Mellor, Pauline Boty The Only Blonde in the World

[3] Sue Watling, David Alan Mellor, Pauline Boty The Only Blonde in the World

[4] Francoise Truffaut, A Certain Tendency in French Cinema, The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks, ed. Peter Graham, Palgrave, 2009

[5] Ken Russell, Altered States, The Biography, Bantam, 1991

[6] Ken Russell, The Lion Roars, Ken Russell on Film, Faber and Faber, 1993

[7] Ken Russell, Interview, Oui Magazine, June, 1973

[8] Ken Russell, The Lion Roars

[19 Ken Russell, Interview, Oui Magazine, June, 1973

[10] Ken Russell, The Lion Roars

[11] Ken Russell, Altered States

[12] Ken Russell, Interview, Oui Magazine, June, 1973

[13] Ken Russell, Altered States

[14] Miles J. Unger, Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World, Simon & Schuster, 2018

©George Porcari 2009

Ken Russell