NOBODY’S VISION: JIM JARMUSCH’S DEAD MAN

Published in CineAction Magazine 2012

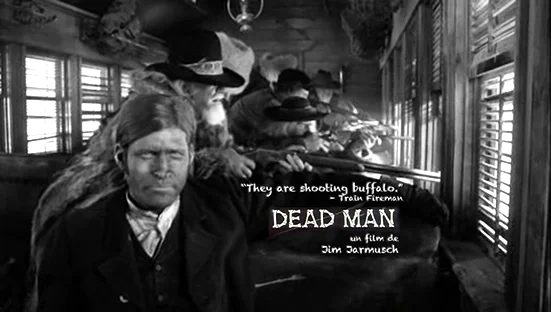

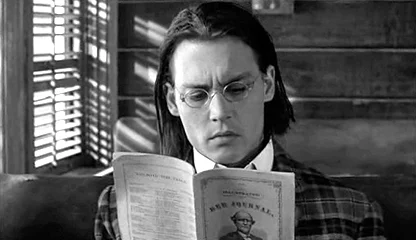

Dead Man (1995) is a film with an original screenplay by its director Jim Jarmusch, the cinematography is by Robby Muller, the DP closely associated with Wim Wenders, and the soundtrack, consisting of improvisations on electric guitar is by Neil Young. Its central character is a clerk named William, or Bill Blake, played by Johnny Depp, who comes west, in an unspecified period sometime in the late 19th century, looking for a job in a town called Machine. Blake’s west is seen first through the slats of a train as it travels through the American landscape in brief tableaus that dissolve to black. We see trash, abandoned wagons, rusting machinery and carcasses left over from the westward expansion. Nature and culture are seen as tied together in an erratic, haphazard cycle of birth, struggle and death; our relation to time, to material things, and to their passing are all articulated in the glimpses of the American landscape we see from the train. The fades to black have an inevitable element of pathos built into their poetics – suggesting that the transient operations of nature and culture together are the fundamental aspects of human social life – such as it is. Significantly Blake is the only traveler to go to the end of the line; his companions on the train come and go, getting progressively more western in demeanor and dress and more destitute and desperate as we reach Machine. When someone in the train shouts “buffalo!” and every man in the train – except for Blake – fires his rifle out the window, we know we have reached an absurd west undreamed of by Frederic Remington, Ansel Adams or John Ford. The onrush of impressions created by the rapid crowding of images from the window of a moving train create an essentially urban sensibility that is then brilliantly grafted to the mythology of the Western.

When Bill Blake arrives in Machine he discovers that the job he came for is taken; the man who informs him is the de-facto owner of the town, John Dickinson, played by Robert Mitchum – a veteran of conventional Hollywood westerns such as River of No Return. As Bill wonders around the hellish streets of Machine he meets a beautiful young woman named Thel. The name comes from Blake’s The Book of Thel, in which a young virgin living in innocence enters the world of experience – not only sexual experience but the world of knowledge and of the senses - only to retreat in terror. Thel invites Blake to her room where she seduces him by asking him to smell her flowers (made of paper). He replies matter-of-factly: “smells like paper.” Mr. Blake, as his city clothes which are too tight, his reading glasses that sit precariously on his nose, and his literal minded answer make clear, is a man ready to discover new territory. Thel comforts Blake in her small boarding room but tells him she keeps a handgun under her pillow because, as she explains sweetly, “this is America.” In the morning, as Thel and Blake lie sleeping in bed, Dickinson’s son and Thel’s sometime boyfriend bursts into the room with a gun and shoots her through the heart. The bullet passes through Thel hitting William in the same spot wounding him mortally. Blake takes Thel’s gun and after spraying the room with bullets shoots the industrialist’s son in the neck and kills him. Then, in the manner of a bedroom farce, he jumps out the window and, landing on his ass, promptly takes the first road out of Machine.

This extraordinary sequence shifting with bravado from the tragic to the comic, from the grotesque to the absurd, evokes the French and German New Waves in its complex counterpoint of styles and emotional content. Bill encounters love and death on his first night in Machine beginning his transformation from Bill Blake to William Blake. The industrialist Dickinson hires three assassins to kill Blake for having killed his son and stolen a horse – the girl’s death is mentioned in passing but not given the importance accorded to the horse. Bill is then visited by one of the most wonderful characters to come out of a work of American film since Oscar Levant, an Indian educated (by way of Mark Twain?) in England named Nobody played by Gary Farmer. In the only flashback in the film we see Nobody as a boy reciting Blake’s poetry by memory to amused and astonished Europeans who treat Nobody as a curiosity, much as musicians and magicians, natives from the colonies in ethnic costume, or sharks in formaldehyde once amused (and still continue to amuse) the very rich. Once he is educated in the ways of white men the traditional Indians wish to have nothing more to do with him. Being too “Indian” to live with whites and too “white” to live with Indians he is caught between cultures, becoming, in a sense, a harbinger of the fate that would await generations of immigrants that came to America. His very language is an amalgam – which Blake at first describes as “Indian talk” – of the traditional poetics associated with the “Vision Quest” of Native American Indians and European poetry. Being neither fish nor fowl his name comes to be Nobody. Having committed William Blake’s poetry to memory he helps the young man, despite the fact that he finds it strange that “William can not remember any of his poetry.” When Nobody sees that Bill has been hit in the heart where the bullet is lodged he presses grass and mud into the wound to seal it. From then on Bill Blake is essentially a dead man. “Did you kill the man who killed you?” asks Nobody. “But I’m not dead” replies Blake. Nobody sees that it is indeed a sensitive poet who speaks, but is it really the William Blake?

Nobody appears to be a man who has seen much and understood that white men bring with them “Machine” – that is a technology that makes life a hell on earth but that white men embrace because they feel it protects them from what they do not understand: Nature. Blake the 19th century poet and British mystic embraced what he did not know – even what he feared - because he saw God manifested precisely there. Birth, death and the varieties of emotions and sense experiences in-between were, for Blake, a mysterious physical force emerging from a totality that could never be understood by men – to try would not only be futile but vane and ultimately self–destructive. American writers as different as Walt Whitman, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, Joan Didion, William Burroughs and Norman Mailer have all written against the American directive to sanitize nature, to control it, and ultimately perhaps to supplant it. All of these writers - Ginsberg and the Beats in particular - railed against the dehumanized organization of American life. Death to the American puritan sensibility is not part of the organic process of life but an intolerable betrayal, an imperfection in the road to perfectibility that must be at best overcome with technology or at worst suppressed – in any case obliterated from view. Dead Man offers an alternative vision in which the hero learns from European art (Blake’s poetry) and from Native American culture (the Vision Quest) to navigate a new and more holistic approach to death and therefore to life, bringing with it an intuitive understanding of our animal and divine nature.

Nobody insists that William confront an encampment of white men sitting around a fire, as if wishing to test Blake’s authenticity as the famed mystic poet. William proceeds to greet the group with strained casualness, but one of the men begins to touch his hair as the other screams: “this one’s mine.” Blake surprisingly kills the men in combat with a certain level of physical grace and professionalism. The corpse of one of the men is seen lying on the ground with his head on the makeshift hearth they had made, creating halo for the dead man, aligning him with the poet Blake's radical spiritual sensibility as the two Blake's bond mystically through the incongruent religious tableau. Nobody comes forward and tells him: “You were a poet and a painter, and now you are a killer of white men.” William Blake is an innocent who presumably had no goal in coming out west (as so many others then and now) other than to find a job. Yet there is something fake about William from the start. It is as if he were playing at the part of a clerk, only half heartedly resigned to the role, and like so many others who came west, had been inspired by reasons that he himself was not fully conscious of. The film charts the progress of Bill Blake into William Blake as he begins to see with the eyes of a poet – albeit an American poet who adapts to his time and place by making poetry with a gun. Ironically Bill Blake himself seems unaware of his own metamorphosis, while the wanted posters that precede him on his voyage chart the changes on his face, in Blake’s terms, from Innocence to Experience. When William sees a wanted poster of himself he seems to have some difficulty recognizing the person in the picture, and sometime later when his glasses are shattered Nobody suggests that he might no longer need them, implying that Blake had up until then not seen the world clearly. With the guidance of Nobody – who in a sense becomes the spiritual guide of his favorite poet – Bill becomes someone who has, again in Blake’s terms, glimpsed something beyond the physical world, and moved to a place where he can see the more fundamental visionary truth that underlies all matter. The film follows this “vision quest” onwards to a Blakean vision of what that visionary truth might look like in cinematic terms.

William Blake speaks to a deputy before he shoots him dead: “My name is William Blake – this is my poetry.” Standing over the corpse of the man he has just killed he proceeds to quote from Blake’s Auguries of Innocence – that he learned from Nobody – “Some are Born to sweet delight/Some are Born to Endless night.” We then see Dickinson hire three unlikely bounty hunters who are enthusiastically introduced as “the finest killers of men and Indians in this half of the world.” This is an inspired, absurdist re-creation of the three wise men: instead of finding the Messiah who is to be reborn after death, they must find William Blake, a man already dead, and kill him. The three not very wise men are “The Kid,” an African American teenager in over his head, Conway Twill a middle-aged talker, and Cole Wilson, the proverbial silent gunslinger dressed in black. Twill explains to the skeptical Kid – without a trace of irony - “Cole fucked his parents and then ate them! Why he ain’t got a Goddamn conscience!” Twill’s unlikely cannibal story is made plausible after Cole kills both his partners by shooting them in the back, and then proceeds to eat the unfortunate Twill by campfire, as we see Cole stripping the meat off a human forearm with his teeth. The cannibal (the consumer to use Blake’s term) figures prominently in the Marriage of Heaven and Hell as the representative of the lower bodily element. In opposition to transcendence he engorges himself without thinking or feeling. For Blake humans possessed both the spiritual and the consumer, who struggled for power within every individual.

Nobody and Bill find a trading post officiated by a cautious Christian missionary who is serviceable to Blake but refuses to sell anything to Nobody because he is an Indian. We are made aware of the catastrophic violence done to the Native American population by white men not through conventional confrontations but through inference: The casual way that Nobody mentions the epidemic of smallpox carried by blankets sold, knowingly, by white traders to the Indian population - one of the earliest instances of germ warfare; the ruined villages that lie depleted and dying, that we see in glances, as Nobody and Bill pass through the American landscape; yet the most telling effect of white men on Indians is Nobody himself – his ironic humor, his hatred subordinated to an almost Buddhist detachment, understanding and acceptance. Such humor could come only after the suffering of many generations, a suffering to exhaustion, to the renunciation of suffering itself because it is inadequate to the reality that has been lived through – a reality in which there are no more reasons to give or tears to shed. Jewish humor comes from a similar place.

Blake realizes that because of the wanted posters on the trading post the Christian missionary has recognized him and he cavalierly takes one of the posters, hands it to him, and offers to autograph it. The missionary pulls out a gun from behind the counter but before he can use it Blake stabs him through the hand with the pen and then shoots him dead. Bill uses the pen – the poet Blake’s weapon of choice – with such agility and street smarts that we see again that it is truly a different person than the one that walked into Machine innocently looking for a clerk’s job. Nobody proceeds to quote Blake to the dead missionary: “The Vision of Christ that thou dost see/Is my Visions greatest enemy.” This damming criticism by William Blake on Christianity is one of many attacks by him on the repeated attempts by organized religion to use rational forms such as stories or paintings to illustrate the divine and to bring people – in the greatest numbers possible – into a passive acceptance of certain rules and orthodoxy. For someone like Blake the idea that you should follow laws established by an institution as a means to reach God – or the spiritual – was absurd. The way to sacred knowledge was not through passive acceptance of orthodoxy, nor blind devotion to the words and images made by those institutions; the way to the divine must be a creative, singular act – it's one on one - it is made through searching, discovery, and passionate action. For Blake there was no other way to realize your own soul and understand its relation to infinity - in short his was an existential relation to the divine.

Nobody and Blake reach their destination: a reservation near the Canadian border that has freshly made totem poles and a craftsman who understands perfectly the sort of canoe Bill needs to reach across “the mirror of waters.” As Bill is placed horizontally on the canoe his energy begins to fade, as he realizes that he is dying, and Nobody appropriately gives him the last push out to sea. At that point we see through Blake’s point-of view Cole Wilson sneak up behind Nobody and shoot him dead. Before dying Nobody uses his last bit if energy to shoot Cole, killing him. The Mystic and the Cannibal upon meeting, destroy each other, exactly as Blake described it in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. This sequence is brilliantly shot in pantomime mimicking the theatrical expressiveness of silent films. The shot also suggest that for Bill this earthly struggle is fading and becoming more schematic. We get further and further away from the shore as Blake is barely able to see above the rim of the canoe. At a certain point he no longer has the strength to hold up his head and he lies back and looks up at the sky. The last shot in the film combines the death of its protagonist with a pan of the ocean at sunset. The exact moment of his death is not seen – it is left to the imagination and becomes imbued with a sense of the natural landscape – a landscape that owes much to the Hudson River school of painting – reminding us that this Blakean view has been transformed into a decidedly American vision. Because of the dramatic use of light, the way it is shot using high contrast black and white, and the psychedelic music by Neil Young, the ocean becomes inevitably a symbol for the source of life, death and re-birth. The water is both a substance that we look at, that we see into, and that also reflects the sky – it is, as Nobody described it, a mirror. The incommensurability of these liquid spaces (air and ocean) expresses the impossibility of apprehending all with the eye or of controlling all with the intellect. The effect of floating on one’s back looking up at the sky is to loose oneself in something that is larger and greater than the self. William Blake gives the impression of floating between the sea and the sky towards a metaphysical space. This state of being is impossible to describe in prose and that is why we have poetry, art and film. This is how the 19th century poet William Blake described it:

The Nature of Infinity is this: That every thing has its

Own Vortex, and when once a traveler thro’Eternity

Has pass’d that Vortex he perceives it roll backward behind

His path, into a globe itself infolding like a sun

Or like a moon, or like a universe of starry majesty.

©George Porcari 2012