ONE SECOND TO LIVE: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF CONCERN

Published in an abridged version NY Arts, May/June 2004

The photograph reveals only a single grotesque or comic moment, I thought, not the person as he really was more or less all of his life. The photograph is a perverse and treacherous falsification. Every photograph - whoever took it, whoever is pictured in it - is a gross violation of human dignity, a monstrous falsification of nature, a base insult to humanity.

Thomas Bernhard

There are only two forces that carry light to all corners of the globe: The sun in the heavens and the Associated Press down here.

Mark Twain

THE BROTHEL WITHOUT WALLS

There are several names for it and it is often seen as a genre that lives within the confines of photojournalism, documentary, or war photography. Some call it the photography of agony (John Berger), some call it shock-pictures (Susan Sontag) and some in social media call it violence porn. In this essay we will call it the photography of concern, after the Magnum agency's phrase "the concerned photographer" that was coined by Cornell Capa who defined it as "describing those photographers who demonstrated in their work a humanitarian impulse to use pictures to educate and change the world, not just to record it."

These are pictures that have been available in the stock photography marketplace for many years and continue to be sold today on the Internet through various sources, both reputable and not. One sometimes sees these photographs of the poor, the disenfranchised, the injured, the dying and the dead on envelopes asking for money with a letter inside that provides a brief explanatory story; one sees them in news magazines that cover a famine or a refugee crisis and there is always an accompanying caption or story that also provides a narrative, usually tied to the current political scene; more recently in the context of social media, where images are disseminated (or decimated) one sees them attached to vulgar or comical phrases or short texts that accompany the images that are meant to be entertaining, amusing or educational; lastly one sees them in the context of fine art in a gallery or museum - the proverbial marble mausoleum - with the inevitable didactic, explanatory essay by an academic, and/or an artist statement that places the images within a codified, prescribed political and social context so there can be no ambiguity or doubt about the strict moral and aesthetic guidelines for exhibiting and viewing the work. The museum space in this essay will be examined in its capacity as an extension of the corporate state apparatus - where various players within the top brass of the cultural ruling elite vie for power - and for that reason it will have much to tell us about their use of images. But outside these gilded halls photography becomes a messy enterprise, a hullaballoo of codes and meanings, a veritable working class swap meet: noisy, flashy, vulgar, cheap, outrageous and of course, mesmerizing. Marshall McLuhan called photography "the brothel without walls" - but what does that actually mean? Was it just a low blow at a medium he didn't take very seriously, seeing it as merely the overture to the main opera to come: television? Let's leave that an open question for the moment.

The Afghan Girl (Sharbat Bibi), 1984 by Steve McCurry

The most famous and the most reproduced of these images of concern, in the 20th century, was taken by Steve McCurry in 1984 and is usually titled The Afghan Girl. It was the cover to National Geographic magazine in June, 1985 and it depicts Sharbat Bibi who was then twelve years old and living in a refugee camp in Pakistan. Her parents had been killed during one of the bombing missions by the Soviet Air Force, then involved in a war with radical Muslim fundamentalists, funded partially by the USA, in an attempt - ultimately successful - to destabilize the Soviet regime and bring it to an end. The second part of the American effort, to provide a stable base of operations for further military action in the area, proved far more difficult to achieve, perhaps impossible. In effect Afghanistan became a proxy war between the superpowers that would continue on long after the defeat of the Soviets, when the religious "freedom fighters" turned on their new masters from Washington, becoming "terrorists." Like many pictures that become iconic it works on many levels at once. As it was first shown by National Geographic it illustrated the refugee crisis, then in the midst of overwhelming the region. For the National Geographic audience Sharbat Bibi was at once a symbol of beauty in the face of war, of life affirming youth in the face of a catastrophe, and of a burgeoning sexuality in the face of immanent death. The image works dramatically on all fronts at once simply and without fuss. Bibi is staring down McCurry, while both of them seem to hold their breath, so there is a perfectly unified stillness to the image - an incredible achievement in the midst of a war that few photographers have been able to pull off.

McCurry emphasizes the chiaroscuro and formal effects of the image, as is his habit, providing a stage of sorts, for the content to speak, but those formal effects are, by McCurry's own admission often manipulated to achieve an effect. "The Afghan Girl" is a painterly image - her clothes refer to a bygone religious, or classical, pictorial history and the contrast of the deep red of her cloak with the green background beautifully sets off her eyes. Unlike most photojournalism all of the extra details, the chance arbitrary elements in the picture, have been eliminated - the work has a clearly religious essence that is without a doubt "artistic." McCurry has, after being repeatedly accused of manipulating his images, come to call himself a "storyteller" or "artist" rather than a "photojournalist" - a not too subtle distinction that we will come back to. "The Afghan Girl" became the most reproduced portrait of the century through postcards, posters, video and ephemera. This essay is about how this "photography of concern" came to be, and why McCurry's uneasy dance between photojournalist, storyteller and artist are important. We start with a brief history of the photography of concern, then move to how these images work in their various journalistic and fine art contexts; and, perhaps even more importantly how they fail to work, and why that failure is more pervasive and unmanageable now as the new century bids farewell to the era of Magnum and the photo-agency - at least as an idea if not as a business enterprise.

Twelve Year Old Boy Pulling Threads in a Sweat Shop, 1889 Jacob Riis

Spinner in a Carolina Cotton Mill, 1908 Lewis Hine

CHILD LABOR

The photography of concern begins with Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, Americans in late 19th and early 20th Century New York, who referred to their photography as illustrations. Riis, a journalist for the New York Tribune, published his first book, How the Other Half Lives in 1890, depicting the slum tenements of New York City and the small, dark, grimy spaces of the very poor - places that many people had never seen became visible for the first time via photography. Hine, working a decade after Riss, for the National Child Labor Committee, illustrated the need to reform child labor practices, using images with accompanying texts. Twelve hour days for children were considered normal then, and Hine followed Riis in attempting to change labor laws by using the inherent realism of photography to affect people emotionally and force them to take action. In a sense their work was tied thematically to other works of outrage, by writers such as Charles Dickens, Jack London and Emile Zola, among others, who wrote about child labor in order to upset their readers and, if not move them to take action, at least make them think about the reality that they were inhabiting in a new way.

Jacob Riis wrote that the first glass plates he took, of a mass grave for paupers in New York, was "so dark as to be almost hopeless, but that the very blackness of my picture added a gloom to the show more realistic than any art of professional skill might attain."[1] The pictures had to be as objective and authentic as possible, and they had to function as a window into the world in order to convey the social truths that needed to be fixed. If people thought that the pictures were false or manipulated in any way - a standard practice from the beginnings of photography that the public was familiar with - they would not be moved to action because they would sense that they were being manipulated. Simone de Beauvoir laid out the ethical problem succinctly in an essay from 1948 on the ethics of ambiguity: "...let us say that a writer wants to communicate the horror inspired in him by children working in sweatshops; he produces so beautiful a book that, enchanted by the tale, the style, and even the images, we forget the horror of the sweatshops or even start admiring it. Will we not then be inclined to think that if death, misery, and injustice can be transfigured for our delight, it is not an evil for there to be death, misery and injustice?"[2]

Riis and Hine equated aesthetics and beauty with fakery and lies - therefore to get to the truth about a subject aesthetics and beauty must be avoided. Of course the work of Riis and Hine eventually produced its own codified worldview, and its own series of aesthetic conventions, that signified "truth" and "authenticity." Subsequently standards of beauty in photography adapted to encompass the images made by Riis and Hine that in time joined the canon of beautiful pictures of the 19th and early 20th century. Within a relatively short time the work entered the marketplace alongside work that they loathed - such as painterly landscapes. In effect the “authenticity” of Riis and Hine become a commodity in the marketplace, alongside other images wanting attention. There seemed to be no escape from aesthetics and commodification even with the high moral standards - that with Riis and Hine had an almost religious sensibility - as practiced by the first photographers of concern. But if aesthetics and commerce could not be avoided, was it possible to put them on hold - to suspend them - and if so how?

Migrations: Humanity in Transition 2000 Sebastian Salgado

SUSAN SONTAG AND SEBASTIAO SALGADO

When standards of beauty changed allowing for the inclusion of photographs of the poor, the sick, the dying, and the dead they started to be shown in cultural institutions, sometimes demanding large sums of money in auction houses, and almost always requiring explanatory catalogs in museums. An ethical dilemma was bound to surface. This was how Susan Sontag articulated the problem with regard to Sebastiao Salgado's photographs, taken over half a century after Riis and Hine, of impoverished, traumatized, exiles on the run, and workers earning slave wages far from first world cities and the oligarchs that employ them: "Sebastiao Salgado has been the principal target of the new campaign against the inauthenticity of the beautiful. Particularly with the seven-year project he calls: Migrations: Humanity in Transition. Salgado has come under steady attack for producing spectacular, beautifully composed big pictures that are said to be 'cinematic.' But the problem is in the pictures themselves, not how and where they are exhibited: in their focus on the powerless, reduced to their powerlessness. It is significant that the powerless are not named in the captions. A portrait that declines to name its subject becomes complicit, if inadvertently, in the cult of celebrity that has fueled an insatiable appetite for the opposite sort of photograph: to grant only the famous their names demotes the rest to representative instances of their occupations, their ethnicities, their plights."[3] Sontag superbly articulated the problem arising from the inauthenticity - or the bad faith - of the beautiful when applied to photographs of human suffering.

Manzanar Street Scene, 1942 Ansel Adams

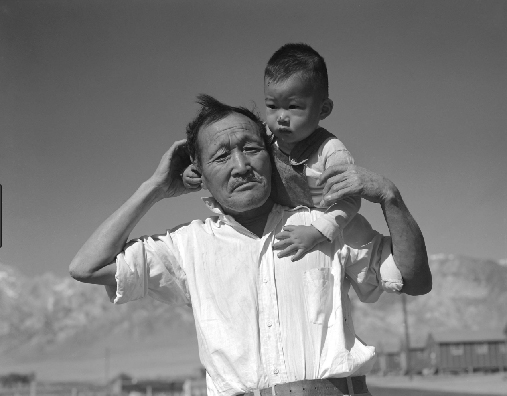

Manzanar, Man With Grandson, 1942 Dorothea Lange

WHAT WE CALL 'BEAUTIFUL' IS A BY-PRODUCT

Unfortunately the problem does not go away with Sontag's well-reasoned argument. The reason is that those who see beauty in scenes of poverty or pain feel that they are not just describing a social condition, or concentrating on scenes of "everyday life," but rather they see themselves as capturing the bigger picture by putting observed reality in its proper perspective. In effect they are seeing more than the "concerned" photographer who only focuses on mere details. When Ansel Adams photographed the Japanese prison camp called Manzanar in California during WWII he saw beauty. Was Adams insane? Was he insensitive to the suffering of the Japanese? Perhaps, but from his own point-of-view Adams wanted to show the larger picture, not the suffering or the despair of certain individuals, as might have been emphasized by someone like Dorothea Lange, who by coincidence was also in Manzanar at the same time as Adams. She studiously avoided the "big picture" and concentrated on individuals and the minutiae of their immediate conditions. With usual bluntness she once said that "I believe that what we call 'beautiful' is generally a by-product." Clearly she was after something else - and that was, to, as she put it, "dare to look at ourselves."[4] In light of this statement it is interesting that many of the pictures that Lang took in Manzanar are still, (as of 2018) classified and not made public by the US government, which owns the original negatives - perhaps still unable to "look at ourselves."

For Adams this "larger picture" that he sought to capture involved Nature - a reality far larger than history. Adams saw human culture and history as elements - at times even minor players - within the context of Nature, that is landscape. Nature is always associated in Adam's work with beauty - there is no such thing as a disgusting, terrifying or incomprehensible aspect of Nature - Nature was always about the sacred. He was not alone in expressing these ideas. Henri Cartier-Bresson thought that "landscapes represent eternity." Adams articulated a philosophical position of transcendence and pantheism, akin to Immanuel Kant's "sublime," but filtered through 19th century American Luminism and the Hudson River School - all aesthetic paradigms that were completely contrary and antithetical to Dorothea Lange's aesthetic and moral vision.

Salgado attempted to synthesize Ansel Adam's romantic viewpoint with Dorothea Lange's socially concerned realism into a logically coherent image that included and transcended both - a bifocal vision that was both a document and an aesthetic object. Along with other photojournalists who specialize in "painterly" effects, such as James Natchwey or Steve McCurry, Salgado emphasizes aesthetics over content, creating an aesthetically coherent, homogeneous display of symbols and types that are readily readable as "art." In their work each genre of photography plays off another as in musical counterpoint, often with spectacular visual force. The problem is that the logic of Salgado's aesthetic is the subject of the work itself, rather than the people in the photograph, who are there, as Sontag argued, as representatives of a certain class, or ethnicity, or both. There is no real synthesis because aesthetics are always the primary player in Salgado'w work, and while the subjects - the human factor - may play a crucial role, it is always secondary. As such they don't need to be mentioned in the credits by name, as Sontag also pointed out, since the work is not really about them, it's about "art." Dorothea Lange is as far removed from Adams and Salgado as she is from the vacant art photography of the postmodern era, such as Sherrie Levine's, that appropriated her work to presumably question the authenticity and integrity of the real, that is ever present in her work and continues to be the lasting source of its integrity, its pictorial intelligence, and its emotional power.

Self-Portrait, 1897 F. Holland Day

Trees Reflected, 1842-43 William Henry Fox Talbot

Le Soleil Couronné, Ocean, 1856 Gustave Le Gray

PICTORIALISM

When photographs of everyday life first appeared in the late 19th century, they were in the minority and attracted little attention. Most photographers, who considered themselves in any sense professional, were using the medium for the scientific exploration of nature, such as the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, who dreamed of marrying science to art and called his pictures "photogenic drawings;" while others, more receptive to aesthetics than to science, were attempting to create images that resembled paintings from various periods, be it a classically staged tableau or an Impressionist landscapes - the two dominant styles of the late 19th century. These painterly photographs were so ubiquitous in photo exhibitions and journals that, as a group, they came to have a name: Pictorialism. This was a movement that was heavily promoted by Alfred Stieglitz's magazine Camera Work (1903-1917). Pictorialists often used gels or blurring effects with soft focus to simulate the effects of painting, as the photographic print was by then very sharp and with a lot of extraneous detail - the world of real life - usually not found in paintings. The Pictorialists carefully followed the rigid program of composition laid out by neoclassical painting in order that their photographs might be considered art as a matter of course. F. Holland Day in his Self-Portrait seems to be influenced as much by Oscar Wilde's Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) as by Pictorialism, with a decadent sense of both upper-class artifice and sexual unmasking, reflecting the then current interests in psychology, the irrational and the instinctive, anticipating Surrealist practice. Some photographers like Gustave Le Gray took landscape photographs that perfectly mirrored the conventions of framing and soft focus peculiar to the painting of the period. Ironically Le Gray had to travel to the actual places that he photographed at great expense and physical danger - something that painters would have to submit to only if they wished it – a situation that ultimately bankrupted him.[5] Others like Oscar Rejlander or Henry Peach Robinson made tableaus that mimicked the effects of 19th century painting – such as those by Jean-August-Dominique Ingres or William Bouguereau – going so far as to create elaborate collages done in the darkroom from dozens of negatives exposed on the same piece of paper – dodging and burning to eliminate the seams and the formal effects of the collage.[6]

HENRY PEACH ROBINSON AND HONORÉ DAUMIER

Let's look at one of these painterly tableaus by Henry Peach Robinson from 1858 - Fading Away - to see how it works. The scene was, of course, staged for the camera over a period of time with not all of the actors being present in the room at the same time.[7} The theatrical lighting, that is not consistent over all of the actors, focuses on the presumably dying young woman - a genre stereotype of the period that had enormous popularity, and a literary wellspring in Alexander Dumas' La Dame aux Camélias from 1848. The sentimentality, evident in Robinson's tableau comes to the forefront to create a facile illustration whose theatricality is referenced in the partially open curtains. Fading Away, the title of the work, is meant to act as the trigger mechanism that allows the sentimental narrative free reign over the image so we may then successfully "read" all of the players and their stories correctly. The characters in Robinson's drama are unfortunately very quickly reduced to highly organized and symbolic tableaux vivants, archetypes that become merely a part of the symbolic order being illustrated, and it is this that becomes the central focus of the work rather than the individuality of the people involved, or the emotional content of the narrative. Unfortunately archetypes more often than not reduce complex realities to the simplicity of an essence – a concept – that organizes the world for us and reduces it to a cliché.

Fading Away, 1858 Henry Peach Robinson

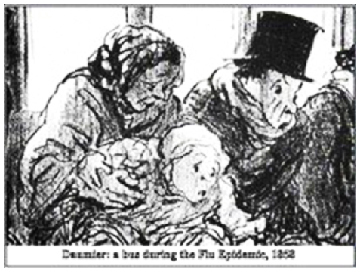

Bus During a Flu Epidemic, 1858 Honoré Daumier

Let’s compare Robinson's tableau to Honore Daumier’s drawing Bus During Flu Epidemic from 1858 that also deals with death in a contemporary setting. The drawing appeared in a journal of the time and was meant to illustrate an accompanying text on the influenza epidemics that killed over a million people, mostly children and the elderly, throughout Europe in the 19th century.[8] Daumier depicts a young family with a baby in a tram, the mother concerned and with a sense of tragic foreboding, the father lost in helpless reflection, and most poignantly the baby looking out at the world in sheer incomprehension, terror, and pain. Ironically Daumier used the norms associated with photographic framing, leaving the right side of the frame cut off, concentrating on the triangle created by the family with the baby at the bottom, acting as a fulcrum. The great photographer Felix Nadar suggested that in the future people would find the drawings of Daumier impossible to believe because his realism would be mistaken for grotesque exaggeration. In fact this is exactly what has happened. Daumier in our time is now taken to have been only a caricaturist prone to exaggeration for the sake of a laugh. Nadar, his contemporary, had a different opinion: "Daumier decisively cuts out these early effigies of bourgeois, janitors and bankers, creatures as strange as Etruscans…(but) which coming generations will refuse to believe in, even though they are, alas!, and will remain, the perfect, daguerreotyped copy of real life in our “Belle-Epoque."[9] In Nadar’s very modern use of quotation marks to signify an ironic overlay of meaning over the word "Belle-Epoque" one can already sense the biting sarcasm – clearly asking, along with Daumier, belle for whom?

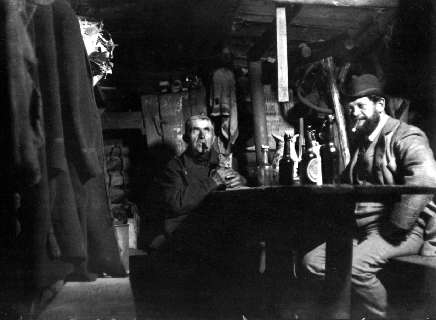

Berlin Bar, 1890 Heinrich Zille

Woman Looking Toward Charlottenburg, 1898 Heinrich Zille

Rue de la Parcheminerie, 1899 Eugene Atget

HEINRICH ZILLE

One of the major photographers of everyday life in the 19th century was the little known artist Heinrich Zille. Giselle Freund: "While Eugene Atget photographed empty streets Zille was interested in their inhabitants. Forty years before Brassai, he photographed graffiti and humorous inscriptions on shops. He never thought of publicly showing his photographs. Moreover, no one would have thought them of any value at a time when only soft-focus photography was fashionable. Heinrich Zille was the first "concerned" photographer, for whom the message his subject conveyed was of most importance. He was the first in a line of incorruptible photojournalists who surfaced later, in the 1930's, and who followed in his footsteps without knowing of his existence."[10] While Zille’s work often used street settings similar to Eugene Atget's - from the same period - there is an important difference. Atget’s magnificent photographs of empty streets foreshadowed both Surrealist practice and formalist photography - a narrative that was in line with a brand of Modernism espoused by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and other institutions that followed suit; while Zille's snapshot aesthetics - a term coined around 1900 to coincide with the Kodak Brownie - that gave primacy to the subject rather than to aesthetic, formal, or "scientific" considerations, did not fit in well or find a place within institutional histories of the medium. To better understand Zille's radical aesthetics, and why it would not fit into any institutional agenda, then or now, let's consider two views of the city from the same general period, that will clarify the matter.

Flat Iron Building, New York 1903 Alfred Steiglitz

Place de Clichy Seen From the rue de Clichy, 1890 Emile Zola

STIEGLITZ AND ZOLA

Alfred Stieglitz's justly celebrated photograph of the Flat Iron Building in New York from 1903 has been carefully cropped by the artist, in the manner of a Chinese ink drawing, to emphasize the verticality of the tree in the foreground and the Flatiron Building behind it in the snow, beautifully orchestrating natural and man-made shapes in shades of grey and white. The image owes much to Impressionism in terms of its formal effects (now reduced to "effects") and to Neo-Classical art in terms of its concept - that is, it is about order, harmony, purity, and essence. The receding benches articulate a barrier between the man made and the natural landscape like a musical staff. Stieglitz's mastery of printing is beautifully evident in the picture as he dodges and burns the image to accent the atmosphere as a thing (snow) and as a mood, a psychic space that we may project ourselves into. The exterior and the interior - nature and culture - are all in harmonious balance. The photograph is as much about this equilibrium as it is about the Flatiron Building.

The image that I would like to contrast with this picture is Emile Zola's Place de Clichy from 1890. The thing that made Zola's photograph shocking, unpublishable, and rarely seen - then and now - was the pile of shit from a horse-drawn carriage in the foreground. Shit was ubiquitous then in urban streets in all cities of the world despite the men paid to follow the carriage routes and shovel it into a cart. The term for it then was "night soil" so more sensitive individuals would not have to say the word "shit" in public. Unfortunately for the population this shit, more often than not, ended up in the city's primary water source. This is John Wright, a London journalist of the period: "...Seven thousand families in Westminster and its suburbs are supplied in water in a state offensive to the sight, disgusting to the imagination, and destructive to the health."[11] In 1890 it was taken as a norm that aesthetic mediums of any kind would rise above the gutter (in every sense) and avoid the shit that was everywhere in the cities of the late 19 and early 20th centuries.

This delicate sensibility of course had class pretensions at its core. Shit was base, common, and associated with disease, working people and the poor. Zola placed it right in the foreground so we don't miss it, and then to add insult to injury (a Zola trademark), he placed humans in the distant background in an offhand manner as if the exact framing and moment of the image's conception had something arbitrary about its construction - anticipating Giles Deleuze's "any-instant-whatever." This arbitrariness is carefully considered and premeditated as it points directly to chance elements as being the centerpiece of the action - the opposite of Stieglitz's highly organized image where every element plays a role. Zola understood that there was nothing more terrifying for a bourgeois audience than the arbitrary or the ambiguous, because it opened the door to randomness as a determining factor in human existence.

Funeral Procession, Rome, 1894 Emile Zola The terror of randomness as a determining factor in human life.

THE PHOTO AGENCY

Photo agencies had existed since the beginning of the 20th century, but the Magnum agency was special. Founded in 1947 from an idea by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and a handful of colleagues, the agency was a cooperative owned and operated by photographers for photographers. The name comes from the famous Magnum champagne that is often used in celebrations and was then also associated with weddings, gourmet dining, and liaison dangereux.[12] The impetus for its creation was to protect photographers from editors, writers and lawyers altering their work by cropping, or using captions to change or even subvert a photographs meaning - something that was by the 1940's a commonplace within the industry. In that sense Magnum would recapture the socialist aspect of the first photo agency - the Danish Union of Press Photographers founded in 1912. That is, to be a union that would represent the photographer, not be at the beck and call of magazines, editors or their corporate bosses. Such unions, at least in the USA, were, for the most part short lived due to violent union busting programs carried out by the state - the most notorious of which came to be known as the Palmer Raids of 1919/20, along with the first "Red Scare," during Woodrow Wilson's time as president. The primary spokesperson for the Socialist cause in the early 20th century in the USA, Eugene Debs, went to prison for criticizing America's entry into the first world war along with many protesters, suffragettes and union organizers. The net result was that the Socialist cause there never recovered its momentum, and was, despite some concessions to larger unions, and the brief ascendancy of F.D.R. and Henry Wallace, effectively marginalized for the remainder of the century.

Magnum was a return to this highly idealistic union enterprise but with the added proviso that unlike previous attempts, that were localized, and often had a nationalistic flavor, Magnum would be international. Susan Sontag: "In Magnum's voice, photography declared itself a global enterprise. The photographer's nationality and national journalistic affiliation were, in principle, irrelevant. The photographer could be from anywhere. And his or her beat was "the world." The photographer was a rover, with wars of unusual interest (for there were many wars) a favorite destination."[13] More to the point Cartier-Bresson called Magnum "a community of thought." That is, not only were the photographers like-minded in their desire to "capture the present historical moment, and perhaps change it for the better," but that for them the medium of photography was itself a way of "thinking with images." Captions and stories would, more often than not, get in the way of this "thought" process. But Cartier-Bresson did not elaborate, and was unclear - or reticent to clarify - how thinking works in terms of photography, presumably letting his images speak for him. To understand why the Magnum photographers wanted their images freed from narrative impositions we must go back to the origins of photojournalism, the revolution of the lightweight portable camera, and the picture magazines that carried their work on a regular basis so they could earn a living from it.

Conference at the Hague, 1928 Erich Salomon

ERICH SALOMON: FIRST PHOTOJOURNALIST

The principal tools that photojournalists use in their work are fast film, portable cameras, and a telephoto lens. Fast films were developed throughout the early 20th century but in 1900 a shutter speed of at least a second or more was needed for a clear exposure indoors without a flash necessitating a tripod. Then a revolution occurred. Ermanox and Leica both developed a small camera and premiered it in 1925 using a roll of film with 36 exposures that were half the size of a conventional frame of film: 35mm.[14} The new film lacked the fine detail and depth of the conventional 70mm format but it more than made up for this by its speed - needing only a fraction of a second to expose indoors without a flash. Erich Salomon at the age of forty one was the first to have the ingenious idea of making a hole in his hat and hiding a small Ermanox inside - at other times the camera was inside his coat or his brief case.[15] Trained as a lawyer and educated in the classical German humanist tradition, Salomon, who insisted on being called "Herr Doctor," could mingle with diplomats and politicians with ease, sometimes sharing a cigar in the corridors of power. Solomon was there when politicians, in a lull between wars, debated the new world order. When a chair was available he would sit and blend into the surroundings. When the Pact of Paris was signed in 1928 by the heads of state who had participated in WWI, presumably ensuring that such a tragic and useless war would never happen again, Salomon was there taking pictures with his hidden camera.

Conference at the Hague, 1930 Erich Salomon

Upon seeing the images that Solomon had caught unawares in 1930, the then foreign minister of France, Aristide Briand, called Salomon the "king of indiscretion."[16] This banal description unwittingly tells us a great deal, for it clearly shows that Briand accepted the idea that journalists would be discreet as a matter of course - and that this formula would apply to "photo-journalists." Salomon had betrayed a trust and broken a convention. His photographs were slightly soft on focus and the framing and angles were sometimes awkward or askew - conventions that we have come to regard as normal for photojournalism and paparazzi photography. The results of Solomon's efforts were immediately felt. Photojournalism of a more predatory kind quickly became the norm and the resulting works became both commodities that could be sold to agencies, newspapers or picture magazines, and a part of the official historical record. Solomon's tenure as the premier photojournalist of his time was short lived due to the war that came, despite the fine treaty. Solomon, a German jew, died in Auschwitz in 1944.

The telephoto lens was invented by German lens manufacturers during the Second World War to be used for surveillance - specifically to survey and photograph the British coast, in an attempt to locate a good landing site for an eventual amphibious invasion. The telephoto lens performed magnificently, but when such an attack was finally launched in June of 1944 it was by the Americans in the beaches of Normandy. In that invasion, where boatloads of men jumped into the water and ran toward a beach where the German artillery was waiting, there was a young, ambitious, Hungarian photographer named Erno Friedmann, who was carrying with him not a gun but a Leica and rolls of film - but no telephoto lens was needed as he was very close to the action. Mr. Friedmann had only recently moved to the USA and wittily changed his name to Robert Capa, after one of his favorite American directors, Frank Capra. Capa always claimed that if your photographs weren't very good it was because you were not close enough, and he was true to his word, getting in the faces of men under fire, and getting his shots. Although much of his work was lost due to an accident at the Life Magazine offices, what survives is perhaps the most intense photographic account of the war.

Normandy Invasion, 1944 Robert Capa

THE PICTURE MAGAZINES

The picture magazine, that is, one devoted to images made from cameras rather than lithographs or illustrations, was established in 1901, as if to inaugurate the century, in Germany with The Berliner Illustrite Zeitung. While photographs had made their way into magazines before then, what made this magazine radical for its time was that it pioneered the photo-essay. Images were laid out in a manner that told a story. Close-ups were placed next to wide angle shots, mimicking cinematic montage, and often there was a beginning, middle and end to stories that would be "read" left to right while turning the pages. The effect was powerful, revolutionary, and would produce like-minded copies elsewhere, most prominently Picture Post in England, Vu (Seen) in France and Life and Look in the USA. With their faster printing methods and cheaper paper, the picture magazines managed to produce very high quality photographic reproductions that could be sold at reasonable prices to the new growing middle classes. In order to compete, most metropolitan newspapers by the 1920's had a weekend supplement heavily illustrated with photographs; something that continues to this day in publications like The New York Times Sunday Magazine.

The picture magazines in the beginning were fresh and new in their democratic approach to images. Gisele Freund: "From this time on, not only celebrities and historic events were to be depicted in the illustrated magazines, but also the life of the man in the street. The illustrated magazine became a symbol of the liberal spirit of the time.[18] Cartier-Bresson, Capa and Gisele Freund - who was a great photographer in her own right - would sell their work to illustrated magazines across the globe through Magnum. While their work, and that of their colleagues, was obviously very good, and at times brilliant, the artist and Bauhaus theoretician Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, expressed some doubts: "There is great danger that demonstrating unmistakably the potential of photographic means will cause an unintended crisis in photographic work in the near future. There will be recipes to produce beautiful pictures without difficulty. What matters, however, is not that photography should become art in the conventional sense, but the great social responsibility of the photographer, who uses the elementary photographic means at his disposal, is to produce a work that could not be created any any other means. This work must the undistorted document of contemporary reality."[19] This prophetic warning did not mean that the photographer would be "objective" or would pretend to be without a point of view. On the contrary - and that is where it gets more complicated. Moholy-Nagy sums up: "The aim is not to be found in the material things themselves nor in the work of art but must be to express the motif in its most succinct and convincing form. If this requires a distorted perspective, then it is because the end has justified the means."[20] But if the end is not in the material things themselves, nor in the work of art, then where is it?

Italian Child in a Refugee Camp, Ticino, Italy, 1945 Werner Bischof

WERNER BISCHOF

Werner Bischof was one of the great photographers of the 20th Century and one of the original members of Magnum, hence one of the creators of the photography of concern. His career began, as many photographers before him, as a painter and graphic artist, then to the School of Applied Arts in Zurich, studying with Hans Finsler, one of the pioneers of Neu Fotografie (New Photography). He was influenced by Surrealism, particularly Man Ray, Constructivism, and cinema, particularly French Poetic Realism, and later Italian Neorealism. New Photography fostered talents as wide ranging as Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Herbert Matter. Its more minor efforts now look like impersonal exercises in a design class. Bischof's work first appeared in Du magazine in December of 1941, when the magazine was ten months old. His editor at Du: "In many discussions we requested or suggested more pictures of people. Be he had to overcome a certain reserve."[21] In 1946 Bischof published his first book: 24 Photos. The first twenty-three photographs of that book represent the best of his early work for Du, which de described so succinctly himself: "Tender maple leaves as if chased in silver, the silky coats of cats, shadow plays projected on to the back of a nude model, snail shells, again and again."[22]

The last photograph in the book Italian Child in a Refugee Camp, Ticino, Italy, 1945 was a documentary image taken in a refugee camp of a young boy - Bischof faces the young refugee head on and there is a beautiful play of light on the boy’s face as he scoops some food into his mouth with an old spoon. The corporeal aspect of the scene - its brutal directness alongside its poetics - articulates a new sensibility and direction for Bischof. Du refused to publish the picture as it did not fit in with the other, more romantic modernist images that were Bischof's stock in trade and Du's main focus of interest. Bischof's reply: "My eyes are opening - I am learning to see. The war came and with it the destruction my "Ivory Tower." My attention focused henceforth on the face of human suffering. I saw this a thousand times over: stranded people waiting for days and weeks behind barbed wire; children and old people and behind them exploding grenades and speeding armored cars. I was driven to get to know the real face of the world"[23] He would wander far from that "ivory tower" and continue to "get to know the real face of the world" taking this kind of picture for the rest of his life, until his tragic, accidental death in Peru nine years later. After Du refused his work he got a job with Schweizer Spende, a Swiss relief organization.

Steelworker, Winterhur, 1943 Werner Bischof

A Country Doctor published by Life Magazine, September 20, 1948 W. Eugene Smith

THE PHOTO ESSAY

The picture magazines were hugely influential in the postwar era throughout Europe and the United States. What made these photographs different from the usual images seen in photo journals was that the pictures were constructed and laid out as narratives from the start, as they had learned from the Berliner Illustrite Zeitung. They were photo-essays that were constructed as such and planned out by both the photographer and the editor, and aside from the German picture magazine, they were influenced by Walker Evans and by W. Eugene Smith's innovative fusion of narrative conventions, adapted from graphic novels and comic strips, but applied to photojournalism. The pictures that the photographers published in the picture magazines and Sunday papers were intensely felt photographs that were seen by the general public on a weekly basis. The approach that the photographers and editors took was blunt and confrontational with both their subjects and their viewers. They were fearless and relentless and the resulting images were often brilliant, direct and profoundly disturbing.

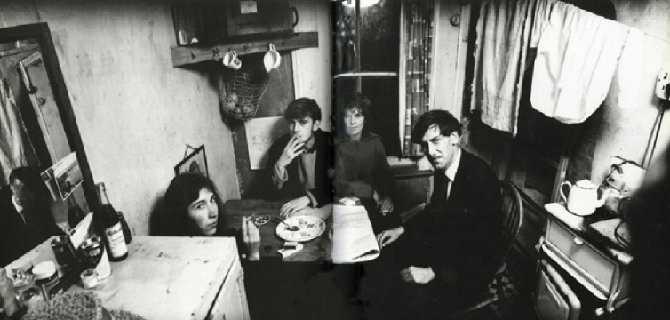

By the 1960’s in England a group of young photographers were called “East Enders” which was a term that not only described a district in London but signified the working class. While previous generations of British photographers, most famously Cecil Beaton, had come from the upper classes, and were featured regularly in traditional journals such as Picture Post and Life, the “terrible trinity” wore their working class origins on their sleeve. A brief window of opportunity had opened in the rigid class system in England that was also happening in art, film, literature, theater and music. These young photographers took on portraiture, journalism and fashion and because of their youth and quick rise to prominence came to be known as “the young meteors”.[7] They shared a similar aesthetic concern with everyday life that was depicted in a way that seemed unaffected by formal or flâneur strategies that, while not completely absent, remained in the background leaving center stage to a content that was often harshly realistic and without a clear narrative arc that explained the action. Their photographs were as direct as a snapshot, an aesthetic that was wholeheartedly embraced. The rise of the young meteors can be seen as part of a larger artistic enterprise in which documentary realism and the working class images associated with it were beginning to permeate all areas of the visual arts. It was not just a matter of working class aesthetics but of ethics hence the resistance from the status quo. The work of the young meteors was also bringing something new: aware of avant-garde cinema and the collage work of the British Independent Group, the first group of artists to consciously create pop art as early as the late forties, the younger photographers were not confined to outmoded conventions and restrictions and were free to experiment and explore more demanding and enigmatic kinds of images. The new work was conscious of heterogeneous and often contradictory emotions and illusive sensibilities that were articulated indirectly or obliquely.

Glasgow: the Unemployed published by the London Times, Photographer: Penny Tweedie

Strippers published by About Town, Photographer: Terence Donovan

A Mission's Failure published by The Observer 1962 Photographer: Ian Berry

A MISSION'S FAILURE

The first photo essay that was most visible to a wide audience, and had the greatest impact, particularly in the USA, was W. Eugene Smith's Country Doctor for Life Magazine, September 20, 1948. While some of the pictures were staged, the players and the settings were real. Smith's clever use of off hand framing - in effect mimicking the effects of documentary work - created a solid ground for his narrative that seamlessly integrated reality and fiction to tell a story. As we can see, Steve McCurry's uneasy dance between "storyteller," "photojournalist," and "artist" were there from the start. McCurry only made obvious - because of his enormous success - what had been the norm since the beginning of the photo-essay. That some people felt cheated or deceived speaks more of their naiveté than it does about McCurry's ethics. From the very beginnings of the medium photographers had been storytellers, journalists and artists at the same time, and they accentuated one or another of these qualities, depending on their temperament, their situation, and the requirements of the job at hand.

The 1950's and 1960's were a high point for the picture magazines, both in terms of radical formal elements and consistently powerful content that far surpassed similar efforts in conventional narrative feature films and fine art photography. Pennie Tweedie, one of the few working women photographers in the post-war era, did a body of work on the unemployed in Glasgow, brilliantly deploying a wide angle lens, stressing the psychological strain of poverty and enclosed spaces for the Shelter in the early sixties.[24} Among the most effective photo stories of the time was Terence Donovan’s series Strippers for the English magazine About Town.[25} The series depicted women who worked in strip clubs, but the pictures were not voyeuristic shots of naked women on stage or in the dressing room. Donovan showed them walking home after work, shopping for groceries or watching television at home. Rather than being objectified, Donovan shot from some distance away, capturing the quotidian social context in which those lives were experienced and so we see who these individuals were and how they lived. In effect the pictures are not about strippers, perse, (despite the provocative title), but about working women in contemporary London, and their struggles, day to day - something that women, and men, could recognize and emphasize with.

In perhaps the most powerful, shocking and effective photo-narrative of the period published in England, Ian Berry did a body of work titled A Mission's Failure for The Observer in 1962.[26] Berry traced a young priest’s journey, first as an idealist ready to save lives and souls, then to his trip inside the slums of South London and his disastrous confrontation with men who were angry, fatigued and who saw the priest as an authority figure that they could finally lash out at. Berry’s work was profoundly influenced by W. Eugene Smith, but Berry also integrated the radical shifts in emotional tone and narrative ambiguities that were common to European films. This disruptive, open ended narrative was completely foreign to Smith, or to the American market that he served. The resulting visual story was brutally honest and direct, capturing the awkwardness and the tensions present in a way rarely seen at the time. For that matter we rarely see this now since this kind of emotionally devastating presentation of reality, with none of the rough edges removed, has never been popular with institutional, corporate or state sponsored enterprises such as those that we can see today in newspapers, magazines, and television that all presumably deal with news or reality in some capacity. With A Mission’s Failure photojournalism reached a high degree of poetics grounded in everyday life that was shocking but also emotionally involving, because the material dealt with poverty and old age not as a rhetoric, as was common in didactic news programs, propaganda and avant-garde practice, but as first-hand observation that held back direct judgment and allowed the viewer space to develop their own ideas.

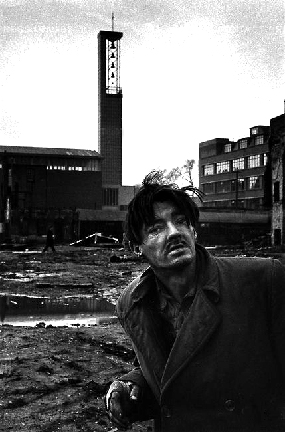

Don McCullin, Homeless Aldgate, East End London, 1963

HOMELESS MAN

A good example of the work of the Young Meteor’s engaging the photography of concern is Don McCullin's ferocious portrait Homeless, Aldgate East London, 1963. This is one of the most successful portraits of a homeless person ever shown publicly. The photograph featured in one of the pivotal scenes in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966). McCullin's brutal portrait suggests a casual snapshot until we look closer. The homeless man's head is caught between the church and the left and the factory on the right - both are in the guise of modernist architecture. This architectural modernism was, ideally, to have liberated mankind from the heavy ornamentation, patriarchy, and repression of the previous century, as well as the dark and squalid factories of the industrial revolution - but from McCullin’s stark image it is clear that modernism is simply another kind of trap. This extraordinary image on first glance might appear to be a snapshot, due to the homeless man's seemingly casual entrance into the frame at an angle, but a closer look proves otherwise. The man, covered in filth and with a bandaged right hand looks thoughtfully at McCullin's camera, that frames his head in a way that pivots between the architecture and the ground beneath his feet. His social condition is illuminated in the landscape that he inhabits due the brilliantly articulate framing. Between the man and this highly ‘civilized”, modernist buildings is a wasteland of mud and debris - again the reality of the man’s day-to-day life is insistently placed within the frame so it becomes a primary motif - the space speaks - it defines a lived historical reality while insisting on the physical, corporeal nature of a man’s life on the streets.

Let us Now Praise Famous Men, 1936 (Two page spread) Photographer: Walker Evans, Text: James Agee

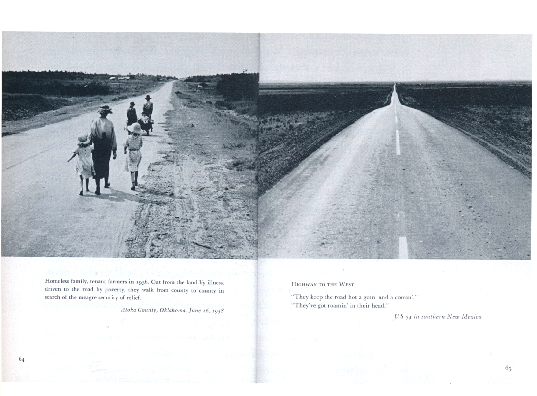

An American Exodus 1939, (Two page spread) Photographer: Dorothea Lange, Text: Paul Taylor

DOROTHEA LANGE AND AN AMERICAN EXODUS

Dorothea Lange's approach to photography was simple and straightforward and she helpfully explained it herself: "Open yourself as wide as you can...like a piece of unexposed, sensitized material."[27] While the picture magazines became progressively more concerned about their content, their audience and their sponsors, photographers turned to the book form as a means of expression. Many of Lange's images would end up with the Farm Security Administration, and Roy Stryker's division: the FSA photographic project, that also involved Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks, and other American masters. There are many superb examples of the photo essay in book form in the period between the two world wars, such as Walker Evans's Let us Now Praise Famous Men (1936), Robert Capa's This is War! (1945), Bill Brandt's The English at Home (1936), or Brassai's Paris By Night (1936). All of these were revolutionary books that brought something new to photography, graphic design, and book publishing. But the book that stands out as the most fascinating is Dorothea Lange's An American Exodus from 1939. Her collaborator on the text, that accompanied every image, was her husband Paul Taylor. Almost all photographic books on American life in this period had a basis in the belief in American exceptionalism. This pernicious idea goes as far back as John Winthrop's "City Upon a Hill" of 1630 - then an extension of Puritan notions that God had chosen Boston as an example, a test, a beacon to the world. These ideas slowly evolved into Manifest Destiny, a feature of 19th century colonialism. Even Walker Evan's book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men hinged on a more austere version of exceptionalism but grafted to Emerson's "self-reliance" and Walt Whitman's "everyman."

Lang documents the rural poverty of the depression but at ground level. Unlike Evans or others working for the FSA she got close, she worked with the poor migrants, the farmers and their families, and she moved with them when they went to California in search of work. A westward expansion driven by economic deprivation as opposed to "exceptionalism" or "manifest destiny." While her image Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California 1936 has become iconic, all of her work dealt with the experiential - the physical, corporeal human being was paramount - and more often than not these human beings were at a crossroads. Lange often catches them thinking, looking for something, or simply making for the nearest road out of town. That was a very peculiar American sentiment - and she got that better than anybody. In American Exodus Lange turned her work into a diptych format that played off one image against another - sometimes the images were very similar suggesting a cinematic narrative consisting of frames very close together in time; at others the pictures were very different, like jump cuts in a film, calling into question the narrative itself. We can compare Lang's radical juxtapositions when we look at Walker Evans and James Agee's beautiful book from the same period: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men that tracks the lives of three poor farming families during the depression. Evans' approach is much more cautious, carefully placing close-ups next to medium shots of the same subject along with text that deals with their story. In An American Exodus images played off the text, not only to illustrate it, but often to wander away from it, and digress into parallel narrative lines. Lang was fascinated by the diptych format and worked with it well into the early 1960s for her gallery and museum exhibitions, but it is in An American Exodus that her work reaches the sublime, playfully juxtaposing multiple, underlying meanings, while retaining, within each image, the foundations of photojournalism. Her feet never left the ground while her visual counterpoint roamed freely over the strong thematic thread, as in American jazz.

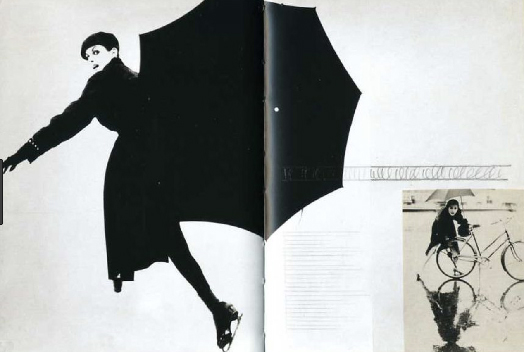

Harper's Bazaar, two page spread Designer: Alexei Brodovich

On the left Equivalent by Alfred Steiglitz 1930 and on the right Scandinavia by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy 1930. Both attempting to make photography into painting but from opposite ends of the accepted aesthetic norms of the time.

Young Boy, Gondeville, Charente, France 1951 Paul Strand The rejection of painting in favor of "straight photography."

STRAIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY

The person that most ingeniously radicalized the formal elements of the picture magazine - particularly within the a-political milieu of fashion - was the graphic designer and editor of Harper's Bazaar, Alexei Brodovich. He brought the radical formal experiments of the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism to bear on Western capitalist products, fashion and editorial work to superb effect. Brodovich, who guided the talents of Richard Avedon and Saul Leiter, used the page like a blank canvas on which to improvise and play. His graphically complex shifts brought a new sophistication to the picture magazines and, while this was seen as something positive, even charming, there was also a negative: Was Brodovich's formula for success tied to Moholy-Nagy's warning of "recipes to produce beautiful pictures without difficulty?" Many called Brodovich's complete eradication of social or historical context into question. But it was Paul Strand who theorized that Brodovich had only taken the ideas of Russian Constructivism, and the Bauhaus, to their logical conclusion, and condemned the whole enterprise as bankrupt.

To put his idea into perspective Strand wrote for Group f.64 that was a magazine devoted to what they called "straight photography," meaning work that was not manipulated but recorded accurately the present historical moment without manipulation or theatrical effects. F.64 is the smallest aperture in a camera, that provides a very wide depth of field, giving a high degree of pinpoint focus and definition to the image. At this f-stop everything is in focus, so one can make a case (and they did) for the "democratization" of the image - that is, a space where everything is equal and so in theory it is the viewer who now decides where to focus their interest. This deep focus would in turn influence Gregg Toland and Orson Welles, in Citizen Kane (1941). This aesthetic formulation was very American, and took from William James’ ideas concerning radical empiricism, that gave absolute primacy to our sense experience, but applied them to photography. For Strand, Moholy-Nagy's images and generally those of the Bauhaus, or the Constructivists, were simply Modernist versions of Pictorialism. They were all in the same boat, but didn't know it. The only difference was that photographers of the old school (Pictorialism), like Stieglitz, applied their photographic efforts to make images that looked like 19th century realist paintings, while Moholy-Nagy and their respective schools, (Modernism) wanted to make images that looked like abstract paintings. In both cases painting was the benchmark. We can see Strand's point in Equivalent by Steiglitz and Scandinavia by Moholy-Nagy, both from 1930, that illustrate his point.

For Strand there had to be a complete break with painting altogether, and a new beginning had to be discovered, acknowledging the inherent primacy and integrity of physical reality over and above that of the artwork, be it realistic or abstract. In short a new way must be found to make art that was peculiar to the medium of photography itself without depending on the 'training wheels' of painting. It was time for photography to stand alone, and succeed or fail on its own merits. Strand's writings, derived in part from Siegfried Kracauer's ideas about photography's mechanical ability to capture the physicality of a particular moment - in the literal sense "capturing the light" (a 19th Century definition of photography) - what Kracauer termed, in his own esoteric language, the "redemption of physical reality." The arguments propounded by Strand ultimately won over the skeptical Stieglitz, who accepted Strand as the new master that picked up where Pictorialism had left off. The last issue of Camera Work - the magazine devoted to promoting Pictorialism - featured Strand's work and those that followed in his footsteps. Strand's ideas were carried over, still later, by Edward Weston, another believer, and had a profound influence on photography, particularly in the USA, where "straight photography" became a dominant aesthetic lasting well into the digital era.

Maguey Cactus, Mexico 1926, Edward Weston

Worker's Parade, 1926 Tina Modotti

POLITICIZED PHOTOGRAPHY

In order to understand how a photographer brings history, and the political, into a photograph let's look at two images and compare them. There are many possible examples to choose from, but there are two examples, from Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, that are exceptional because their relationship, as photographers and as people, was close. Not only were they, for a time, a couple, but Weston was also a teacher who lent advice and camera equipment over a span of many years to the younger Modotti; when their sexual relationship ended they remained friends and their letters remain a testament to two people who, despite strong political differences, remained close. I would like to contrast two pictures from 1926 - both textbook examples of Formalist photography - that is, work that is Modernist, taking from Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism, but also accepting the American ideas that would in a few years come to be known as "straight photography," from F.64 and the work of Strand.

The results are classic pictures by two master photographers, but there is a major difference, and that difference is politics. Weston's Maguey Cactus, Mexico 1926 depicts a plant that takes up the whole frame - one of the many giant cactuses that populate the landscape of Mexico - its incredible silhouette an ambiguous life force reaching out toward the cloudy sky. The interplay between the sensual, somewhat intimidating, formal qualities of the cactus and the literal plant in the ground beautifully play off each other, as in musical counterpoint. Nevertheless the picture is completely a-political - it isn't meant to be political in any sense - Weston very consciously uses all of his skills to focus on something "ordinary" and turn it into something extraordinary. His partner, Tina Modotti, has also taken a highly abstracted, formal photograph - Worker's Parade. Modotti foregoes the careful, pinpoint focus that Weston favors, but her work, shot from far above looking down, as if flying over the large group, charges the image with history and politics, as if it had been hit by lightning. The workers, all wearing similar hats covering their individualized characteristics, move as one solid mass - the "specter of communism" that Marx described at the beginning of the Communist Manifesto was never more beautifully articulated in photography. How did Modotti do it? It is not simply a matter of a different subject matter between Weston and Modotti - cactus and workers - it's in the emotional connection that each brings to bear on the work. In her photograph Modotti is simultaneously with those people and removed from them - her heart is right there with them, but she doesn't get too close - maybe she even backs off - it's the extraordinary vulnerability that makes the shot, and that charges the politics with a subtle but powerful emotional force.

W. Eugene Smith A Country Doctor, 1948

John Ford (frame still) Young Mr. Lincoln, 1939

As we saw earlier the photo-essay that was most visible to a wide public, and had the greatest impact, because it was so new to its audience, was W. Eugene Smith's Country Doctor for Life Magazine, September 20, 1948. Smith traveled to the small town of Kremmling, Colorado to photograph a young doctor, Ernest Ceriani doing his job. While some of the photographs were staged, they still corresponded to Ceriani’s actual job, but were merely framed in more photogenic tableaus that were easily readable. Smith shot the series - using a 35mm camera - with a humanist narrative in mind. The Encyclopaedia Britannica called him a photographer who was “characterized by a strong sense of empathy and social conscience.” But Life Magazine, under the tight directorial hand of Henry Luce, had different ideas about how to present Smith’s narrative. Luce was an autocrat who favored corporate control of the state and a consensus culture, that placed the USA, and what he termed “The American Century,” as a guiding light with a strong military presence that used the carrot and the stick in equal measure. America was to be the only superpower and once relative control was assured it would not be relinquished at any price.

Luce believed, as did many before and after him, that America’s business was business, and anything that got in the way of that ideology was an enemy to be subsumed, marginalized or destroyed. Luce, like many politically engaged businessmen, favored Walter Lippmann’s approach to the the population at large, considering them a “bewildered herd” (Lippmann’s term) that must be guided by a strong leader/father figure who would be the at the top of a hierarchy that he called the “governing class.” According to Lippmann’s book Public Opinion (1922) this group would in turn be beholden to a “specialized class” of well educated elites and oligarchs. In effect the modern world was becoming too complex for the ordinary citizen to make any thoughtful, considered decisions - it must be done for them - but the citizenry must retain and enjoy the illusion that their elected leaders represent them as individuals (not as a class). The oligarch’s of the gilded age may have had their small differences but in the areas devoted to business and profit they were of one mind - and despite the depression of 1929 they carried on with only a few concessions to Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal.”

Life placed Smith’s narrative within a politicized framework, brilliantly leaving out the word politics from the program, letting the emotional charge of Smith’s narrative do all of the work. Smith’s essay was published “the same month that the Truman administration announced plans for national health insurance. Along with the American Medical Association, Life viewed federal interest in the health of its citizens with suspicion, particularly as compulsory health insurance threatened organized medicine’s stranglehold on American health care. Life used the photo-essay “Country Doctor” as an “ideological tool” to help brand such proposed Fair Deal social benefits as “socialized medicine” and hence, a “threat to American Freedom.” Their journalistic lobbying helped kill the Fair Deal plan for national health insurance.”(28) By carefully placing stories negative to the Fair Deal (Truman’s version of Roosevelt’s “New Deal”) with Smith’s photo-essay Life created an emotional montage - in effect a supra-narrative or meta-narrative that would not negate or supplant Smith’s humanist story but subsume it and integrate it into a larger narrative of "consensus culture.” What was that narrative?

While Smith’s humanist intentions are plain and transparent the narrative that Life emphasized was invisible - assuming the pose of being a succession of images and stories that are together through pure chance - a similar technique in use today in the world of television broadcasting. But the magazine’s use of Smith’s photo-essay was one more proper to a John Ford film - such as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) - where a loner, who is a “good man” comes into a town (or a country) and saves the population from some natural or man made catastrophe perpetuated by “bad men” using his street smarts, iron will, the love of a “good woman,” and God’s help. The emphasis was on freedom of action, wide open spaces, and most importantly here, transactions that involve only a handshake and a man’s word. In short Life grafted the mythology of America and the West to Smith’s “country doctor” in modern day Colorado to create a narrative of redemption. In Life Magazine’s careful layout, Smith’s story of a doctor who doesn’t need the meddling of social contracts or socialized medicine to make house calls and do his job was followed by an attack on the “Fair Deal.” This was an inventive, powerful method for creating a meta-narrative that subsumed the smaller (Smith’s) humanist story like a parasite that eats its prey but leaves the shell of its surprised “host” intact. The “Fair Deal” was defeated that same year and the ideals of socialized medicine would not recover to the present day (2018). The fact that average, tax paying, Americans would vote against their own self-interest showed the immense power of the Life photo-narrative, and their astute use of Smith’s humanist storyline. While Luce was clearly a pathologically, self-serving oligarch, his approach - successful on all fronts - would become a template not only for future storyboards in Life, but for other publications such as Fortune (also owned by Luce), Time and Newsweek. This same template would later be used in the new format of television and their reporting of “objective” news stories. The montage of images to create powerful emotional narrative arcs was the key to manipulate the masses to the point that they would disavow their own interest in favor of myths and stories that were in essence fantasy narratives.

In Giselle Freund's writing it is clear that the hopes for the picture magazines were high but the results were more often than not disappointing, especially as the economic depression and militarization of the thirties polarized much of the society. For the picture magazines, the narrative logic and calculated juxtapositions of magazine layouts dictated by editors and art directors elicited a strict and consistent narrative through cropping and captions that provided a readily understandable overall meaning, or concept, that often dehistoricized images. This made the layouts analogous to propaganda, advertising, or Hollywood films, whose primary purpose was to educate, entertain and reassure. It is ironic that images which were presumed to stand on their own beyond art historical, linguistic boundaries or concerns were at the last moment reined in, or hijacked, by text, and in a sense made to play a supporting role to narrative. If an image was in any way shocking because of its violence, it was made very clear through captions and text what the context was, where responsibility lay, and what moral we might take with us in order to become better human beings. In short, it was not necessary to think about the images being presented because they had been thought through for us. Photographs in the picture magazines were systematically typecast and packaged to fit pre-existing formulas. Lacking in specifics, because there was no room for historical analysis, they concentrated on generalities that reinforced or boosted narratives already in place, such as those associated with patriotism or family values, and then set them in a "modern" context that would make them palatable.

Back to Fort Scott, for Life Magazine (unpublished) 1950 Photographer: Gordon Parks

Speaking of Pictures... for Life Magazine June 12, 1950 Photographer: Robert Doisneau

The picture magazines also tended to rely on successively more banal "human interest" stories to fill their pages, at the expense of socially relevant or historical images that might upset a certain number of their readership. For example, Life Magazine in 1950 commissioned Gordon Parks, the first African American to work for Life, to go back to his home of Fort Scott, Kansas and take pictures and create a photo essay.[29] Parks went deep into Fort Scott, even following the stories of those who had, predictably, moved north to Detroit and Chicago to find work. He managed in a very short time to put together one of the most fascinating and historically important photo essays of life in the USA just before the civil rights movement changed everything. Parks knew Fort Scott well and got incredible, unposed, intimate photographs of people in the midst of a radical historical transformation - the coming civil rights struggles. Those were some hard looks that Parks got, and he didn't flinch - he looked right back at his subjects and he got his shots. Life Magazine cancelled the photo-story before going to print, perhaps in order to not offend the large numbers of white readers in conservative parts of the country, and the images would only be published by Steidl Press in 2015. The same year Parks was in Fort Scott Life published a banal photo-essay of people kissing on the streets of Paris, featuring the pictures of Robert Doisneau, who would become famous thanks to Life's vast readership. His picture of a young couple kissing in front of a cafe would become one of the iconic images of the century. The photograph was staged but used real people instead of models, and real locations with natural light; Doisneau also shot from some distance away, as if he had happened upon the scene by chance, delicately balancing art, storytelling and journalism. The French photographer’s charming, but slight, photo-essay was what the photo magazines were turning to with greater regularity making it difficult for more progressive or radical content to gain exposure.

South Africa and its Problem for Life Magazine two page layout September 18, 1950 Photographer: Margaret Bourke-White

On the left Robert Capa's original image Spain 1936 (unpublished) and on the right the edited version by Vu magazine (published).

The picture magazines would, at times, completely undermine the work of photographers, crippling their work, deliberately creating new meanings enforced by editors and owners. Few photographers had recourse but to accept the situation. Two examples: Margaret Bourke-White's extraordinary photo-essay, South Africa and Its Problem dealt with the apartheid situation in that country, and was published in Life Magazine, September 18, 1950. This stark, beautiful, series of black and white images is made to co-exist with advertising - using color photography - that detracts from the power of her work, cheapens it, and creates an equivalence of images - a faux democracy - that undermines Bourke-White's powerful narrative for Life's own: the triumph of capital and the marketplace. Secondly, Robert Capa's original full frame image, of women during the Spanish civil war, Spain 1936, shows them clearly raising a clenched fist, a salute well known at the time signifying allegiance to the Communist cause, and often given while singing the "Internationale" (as was the case here) - the anthem of Communist solidarity. Vu magazine's cropping for their issue of 1936 eliminates the details that provide a social context, basically de-historicizing the photograph and turning it into an image of banal tourism

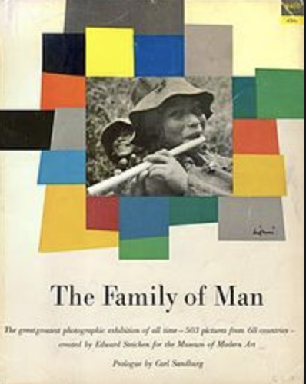

Catalog for The Family of Man Exhibit MoMA 1955

THE FAMILY OF MAN

The kind of photography associated with the picture magazines, including the photography of concern, reaches a kind of zenith of approbation and self-congratulation in The Family of Man exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955 under the leadership of Edward Steichen. It was then and remains today the most visited exhibition of photography in history. Composed of five hundred and three photographs under various categories such as birth, love, food, children, and death, the exhibit brilliantly anticipated Marshall McLuhan's "Global Village" theme, but also reinforced the predictable and parochial narrative logic that the picture magazines had been espousing for years. It would remain for independent photographers of the same period, such as Robert Frank, William Kline, Helen Levitt, Mario Giacomelli, Nacho Lopez, and others to put messy History back into photography with a strong pictorial voice.

As the picture magazines became progressively more conservative in subsequent years, they declined and eventually disappeared, subsumed by television. But the primary reason for their disappearance was not their turn toward conservative politics. With the exception of the French magazine Vu, that had a socialist or liberal bias, all of the photo magazines had been conservative, that is catering to the ideology of the ruling elite, from the start. Rather, their decline was predicated on the fact that their primary source of revenue, which was advertising, moved to television because for the same amount of money spent, advertisers could reach a much larger and more demographically accurate audience, therefore more receptive to their product. The picture magazines from their beginnings had close links to their respective government representatives and corporate sponsors. In one well known, and very ironic example, the Soviet Building the U.S.S.R., promoted by Stalin's cultural bureaucrats, and the American Life, promoted by Henry Luce and the corporate establishment, had a similar message that they sought to convey via their respective picture magazines regardless of the content - this underlying message attempted to sway what the Americans would later call "perception management:" In terms of content, they both sought clear and simple moral lessons with an emphasis on hard work, patriotism, boosterism, economic progress, and traditional family values; and in terms of graphic layout both sides favored a homogenized and immediately legible aesthetic that could be easily understood on a first read.

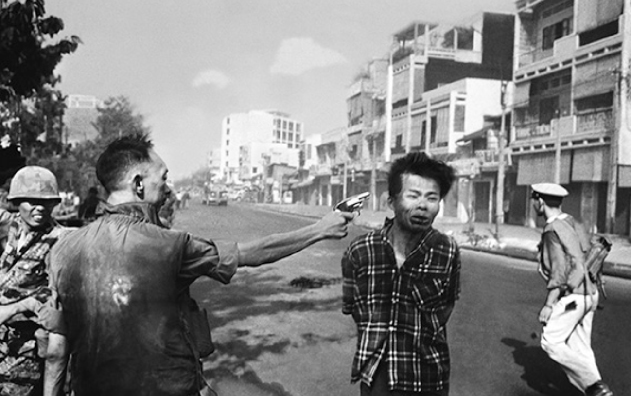

Murder of Vietcong by the Saigon Police Chief, 1968 Eddie Adams (Full Frame)

Murder of Vietcong by the Saigon Police Chief, 1968 Eddie Adams (Edited Frame as published)

ONE SECOND TO LIVE

On looking at Eddie Adam’s photograph of the Saigon chief of police shooting Vietcong officer Nguyen Van Lem in the head at point blank range on a Saigon Street in the middle of the day on February 1st 1968 we can see many things. The image is justly famous for its dramatic power – getting inside the historical maelstrom of 1968 - and there is much that we can learn from it regarding the meaning of images and their cropping.

In the original un-cropped photograph there are not two men but four. On the far left is a soldier in full camouflage gear and helmet appearing to move forward with some urgency and on the far right is a man with a white cap and pants, strangely oblivious to the scene, running across the street. These two men act as a kind of parenthesis to the central action – while between the two main protagonists a nameless Saigon street recedes into space with various kinds of architecture, from different periods, haphazardly butted up together. There are some puffy white clouds in the clear sky. The scene evokes not simply a ritualized murder in wartime but the very impossibility of fixing time except as a membrane in space that, in all of its complexity, remains unknowable, mysterious, and without labels that we may attach as explanatory markers. We are lost in space in this photograph, to say nothing of time. Captions provide a buoy of sorts in the rough seas but they can barely control the power of the image – and this comes not only from the obvious drama, but from the arbitrary elements within the frame that destabilize it, and this arbitrariness is also one of the key elements by which we come to recognize the snapshot. The published version of the photograph eliminates this snapshot element and re-composes the shot so we get only one clearly defined narrative.

But the full frame tells a different story. Adams didn’t have time to compose his shot or wait for the "decisive moment" – he focused his camera on the gun and hoped for the best. What do we see besides a man who has one second to live? What does that one second look like? We see many histories coming together: the history of Nguyen Van Lem as a Vietcong assassin who has only known war, first with the French and then the Americans - and now he is about to die; the history of the chief of police, caught between Vietcong and American atrocities - perhaps already dreaming of his eventual exile in the suburbs of California; there is the history of the man running across the street away from the immanent murder; of the soldier seemingly reaching out towards the action but it is unclear what he means to do; and of course the history of Adams himself as a young photojournalist in Saigon in the middle of what Life magazine called “the story of the decade.” Adams’ picture got their intersection – and time is flowing in many directions, not one. What the image gets is the poly-temporal aspect of the scene and the frozen tableau – one playing off the other. The snapshot aspect in this respect is absolutely crucial as snapshots treat time as a fragment, a membrane, an immersive liquid, a circle that expands outward in many directions at once – rather than more composed tableaus, as we see in the edited version of the same photograph - where a narrative line that comes from one direction (the past) goes directly to another (the future) and is determined by it.